|

archived writings on music: part two (July 2009-December 2009)

older

posts (Jan-Jul 2009) / current page / newer

posts (Jan 2010-May 2011) /

Contents of this page:

They Laughed When I Started to Play... /

Bless the recording stars and

the children /

Civil War / Dialogue with a Steinway / I'd Like to Thank the Academy /

Precedent /

An Exercise in Creative

Ignorance

They Laughed when I Started to

Play

posted December 2, 2009

They Laughed

When I Sat Down at the Piano, But when I started to

Play!~

--famous ad for U.S. School of Music, 1926 by

John Caples

A couple of months ago, during a performance, I had

one of those moments onstage where everybody was

laughing at me. You've probably experienced

something similar in your nightmares, only this was

actually happening. And I loved it.

The piano recital is a strange institution. Most

people have never been to one. It may seem stern and

forbidding. Somehow the idea that you are supposed

to sit and listen to something you can't sing along

with causes people to stay away in droves. And it is

not easy to get people to be quiet and listen to

music. Darwin was mystified why we had music at all

since it does not seem to be a survival skill. The

other night at a special church service I attended

we were asked to listen to the organ Postlude rather

than getting up and conversing with one another. It

nearly killed some people to do it, judging from the

fidgeting in the second row.

I've always imagined that the reason for such

solemnity wasn't the solemnity. It is a simple

matter of respect. If someone is talking to you, you

listen. If that somebody is a piano, you also

listen. But if someone says something that makes you

want to react, you react. Civilly, of course.

Hence my amusement at the performance. I was

playing a splendid piece by William Albright called

Grand Sonata in Rag, which is basically a fusion of

classical and ragtime elements, or, as I called it

at the time, high-octane rag. During the last

movement there is a little joke in the music,

and--they got it!

You need to know your Wagner to get the whole point

of the joke, but even if you can't quote Das Ringen

Der Nibelungen chapter and verse, the way the music

suddenly shifts from ethereal, cathedral echoes to

pedestrian street banter without a bar's warning is

self-evidently very funny. Suddenly, the

introspective, contained world of the

quasi-religious prayer from the world of opera is

shattered by a wild return of the boisterous rag,

and, just as suddenly, the genie is back in the

bottle. For a phrase, anyway.

Several times during that section the audience gave

forth torrents of healthy laughter. I wish I had a

recording. You could tell they were in the same

room, and that they were enjoying the proceedings.

It was very communal!

At another concert recently I mock-apologized to my

audience on behalf of all us concert pianists who

force the audience to sit still while playing music

that makes them want to dance. It is another case of

having to reign in our instincts. It is also too

bad, because, like many of life's conundrums, we set

the rhetorical bar too high. Several pianists I've

read or heard from have spoken up recently in favor

of being more audience friendly. It seems that

artists have spent so much time trying to get the

audience to behave decently (often by bullying them)

that what results is a culture of fear, rather than

respect. Keeping quiet because you want to

understand and communicate with the music is not the

same thing as being quiet out of the fear that if

you dare to make a sound, people will look at you

like a leper with hemorrhoids. Unfortunately, some

of that rests on the ability of the audience to know

the difference, and they just don't seem to get the

memo. Just how do we get people to shut up without

clamming up? To recognize the need to let other

people listen (and that requires unanimous

participation) without feeling like we have to

hermetically seal the experience?

For a moment during the performance it didn't

matter. Mr. Albright told a joke, people laughed. Of

course, the delivery helps a little, and the set-up.

I had a theory professor who did that very well. She

could have people laughing at a Beethoven string

quartet. And why not? What people think of as

serious music was usually written by people with

great senses of humor. Bach? He could be very funny

sometimes. Beethoven? Quite the jokester. True, when

he is serious he is profoundly serious. But that is

hardly always the case. Mozart? Well, we know he

could lay on the silly on many occasions. Brahms?

Well, he may actually be the most serious of the

lot, by and large. But even he had a lighter side.

Once at a lecture given by my theory professor she

had the audience laughing during a piece by Samuel

Barber that I played (I was 'illustrating' the

lecture, ie., she was talking about the pieces and I

was playing them). It wasn't because Barber

announced that the piece was meant to be funny--it

was because, at that musical moment, something

happened that we'd been led not to expect, and

happened with a vengeance! Having been given

permission to laugh by something she said earlier,

the audience interpreted this musical misdirection

the same way they would have interpreted it had it

been in English. The same way being surprised by a

pun or hit between the eyes with a comic

misunderstanding between two characters in a joke

causes us to break into laughter. Musical syntax can

work the same way. The way the unexpected breaks

into the routine can either be a revelation, or it

can be risible.

It's just that we are afraid, sometimes, because we

think that art is sacred. And sacred isn't funny.

I'm not sure where we've gotten that idea but I know

it is basic to a lot of us. Several years ago I

played the same Albright piece before an audience of

undergraduates at my school. They seemed to be

maintaining a respectful silence. It was one of the

most depressing performances of my life. It turns

out they were laughing, but the concert hall was so

large I couldn't hear them. Afterward I got an

ovation, and lots of enthusiastic compliments. One

of my students said I was 'Da Bomb,' which I really

ought to have in my publicity material. Newspaper

reviewers are really too polite (even when they are

exaggerating their praise).

What we really mean when we call

art music 'serious music' is that our aims our high.

The composers were trying to do more than simply

entertain us, simply pander to our current notions

of what is good and what is not good, but to engage

us. To stretch our boundaries, to get us to see and

hear more than we did when we entered the room. That

doesn't mean that levity is not in order. Because

this, too, is an essential part of what makes us

human. Ignore that, and you've left part of your

soul at the door.

Bless the recording stars and

the children

posted October 31, 2009

Everybody has to be a star.

In the spring it's usually the birds. They don't

have to start from scratch every year like some

other critters, and, like star performers, they come

prepared to sing their favorite arias almost

immediately. They are quick studies, and they know

it, and they want you to know it. And to know they

know you know it. And they sing loud.

The reason this is an issue is that I have my own

recording equipment, and will often drop in a

recording I've made myself on this website. It loses

something in sound quality, particularly if I

haven't figured out where to put the microphone, but

it gains something in not having to book studio time

or be especially prepared with a piece I'm just

learning (if it's no good I can throw it out and

haven't lost anything). I'll probably replace most

of the amateur recordings on this site with

professional ones sooner or later, though every once

in a while I get lucky and the results aren't too

bad. But do those darned birds have to be in it? It

is usually solo repertoire, after all. I tried

explaining that to them, but they don't seem to

care.

From about mid-July through October, it is the

crickets. There is one that takes up residence just

outside one of the windows in our church sanctuary,

and likes to keep time. Actually, it's more like one

of those avant-garde experiments with going in and

out of phase that was popular in the 60s.

Cricket-phase, I think.

You can hear the resident cricket most prominently

in a recording of a strange little piece I made four

years ago of Erik Satie's Prayer For the Health of My Friend

from Mass for the Poor. I imagine many of my friends

could use prayers for their health these days, as do

I. That virus (not the flu) that seems to be the

very thing these days (all the kids have it) has

given me a lot not to be able to talk about.

Besides that recording for piano and obbligato

cricket, there is that prelude I played earlier this

month by Michael Praetorius. I started

the month by playing 400 year old organ music from

Germany. More recently, I've been posting ragtime

(without much comment from my supporting cast of

creatures). On the Praetorius recording you can hear

birds chirping about 5 minutes in. This is partly

because I positioned microphone in the back of the

church, because up front it was getting sounds from

the organ's playing mechanisms that was disruptive.

The sound seems to be better in the back. I guess

the birds think so too, which is why they've got a

nest back there.

Not that the birds or the crickets completely drown

the organ; they are not really that much worse

behaved than the average symphony audience. For real

disruption, though, you can't beat the experience of

one of my teachers while recording a CD

professionally in Cleveland. They chose Labor Day

weekend for the event, which is, if you are trying

to record something in Cleveland, a very bad idea.

Cleveland likes to host a little thing they call the

Air Show every year at that time. I don't know

whether everyone concerned realized this before or

after the Blue Angels made their first pass over the

recording studio. But it did cause some stoppages in

the sessions.

I guess I shouldn't get that worked up, then, when

somebody drops a pile of lumber in the sanctuary

during a recording (in case you wondered what that

loud noise was near the end of Summo Parenti Gloria. That

recording also dates from my first year in Illinois,

when we were having the roof replaced. One of my

first times practicing the organ in our sanctuary

featured some tiles being dropped on the roof right

above the organ. It sounded like Armageddon

localized directly over my head. Particularly since

I didn't even know they were up there (why couldn't

I get a still, small, voice?).

By the way, I should mention that the

Champaign/Urbana area has suffered a plague of

ladybugs recently. I don't mind them that much. They

are well-behaved, meaning they don't make any noise,

and they generally go about their business, which is

a pleasant mystery to me. They actually seem like

they are in town for a convention rather than

plotting a blight on humanity. Currently they are

just having meetings about it. If I were Pharaoh,

and Moses gave me a choice of plagues, I'd go with

ladybugs. We've had gnats already this year, and

they are far more of a nuisance.

Winter is coming, and with it the

lesser challenge to recording sanity. The crickets

will stop chirping--even they have grown tired of

meditating on the same note night after night. The

birds will be at their time shares in Florida; the

only sounds will be the constant humming of the

heating system, filling in the awful void that

actual quiet might create. I have a way to filter

that out in recordings, though, but if I have to do

too much of it is distorts the sound. I'm not

complaining about the heat, though. I used to have

to play in winter with a heavy coat on. I can still

attribute the missed notes in an early recording to

the stiffness of the coat I was wearing at the time.

Of course, there was that recent recording I made

with a fly buzzing around my head (that takes

concentration!)--one of my sessions was interrupted

by a couple of guys coming in to change a light bulb

(twenty feet above the floor). Life goes on, in

endless variety.

Some days incidents like this are

just funny, but we are taught to be goal-oriented in

this society, and there are times I just want to

make a decent product and not spend all morning

trying to get it to go. I'd prefer to record without

the constant comments from nature's peanut gallery,

just as I'd prefer not to miss notes. But I'm

reminded of a Muslim quilt maker who intentionally

mars each of his creations because it reminds him

that only God is perfect. I don't have to try,

usually. The mistakes happen, and the crickets want

to be backup singers, and it provides an interesting

diary of what time of year it was and what I was

doing with my life at the time when I listen to it

later. I've noticed several of the recordings I made

while in Baltimore have sirens in the background,

because you couldn't go thirty seconds without an

ambulance screaming down the street. Humanity puts

out a lot of noise, particularly when its members

are in trouble. But the birds and the crickets go on

singing whatever their lot. Come to think of it, so

do we.

"Civil" War

posted October 5, 2009

A few months ago, while writing an article about Schubert,

I flippantly presumed that there was no book called

�musical composition for dummies.� I was making the

point that a creative act does not lend itself to

having an answer key in case you get stuck. It is

not like 2 plus 2, with an answer that is knowable

and identical for anybody who bothers to find out.

The way you get out of a creative jam is you figure

out what the answer is yourself, because each piece

is different. There will, of course, be traditions

to which you can refer, and great composers of the

past whose works you can study; no piece exists in a

vacuum. But any truly artistic effort will succeed

on its own terms�the shape of the piece determined

by what you are trying to say through the contents

of the notes, and vice versa.

But I thought, while I was at it, I�d better look

and see if somebody had indeed written a book called

�Composition for Dummies.� Turns out, they had.

Somebody had written a review of it, and they

weren�t all that pleased. I haven�t read the book,

but I imagine it does contain some of the simple,

recipe-like formulas that I stated were not what

creativity was really all about. The sorts of things

that could allow just anybody to write music by

learning a couple of simple ideas and then basically

coloring them in. It is, after all, for

self-identified �dummies.� You don�t start a course

on �Math for dummies� with long digressions on

Differential Calculus. First you have to be able to

add.

The reviewer focused on some things that he felt

were just plain wrong factually, and suggested, that

if the book contained so many errors in things he

knew, what else might be wrong in things he didn�t?

These things probably will strike most

non-advanced-degree holding musicians as picky, but

I think they hold water. The first had to do with

the book�s definition of the development section in

sonata form. Quoting from the book (on page 148) he

wrote:

"The development often sounds like it belongs in an

entirely different piece of music altogether -- it

is usually in a different key and may have a

different time signature than the exposition."

A little definition may be in order here. Most

Symphonies, Concertos, Sonatas, and so forth,

contain several �movements.� To the uninitiated they

may seem like merely a group of pieces, though they

are usually related in a number of ways. The first

of those �movements� usually is cast in �sonata�

form. This means that it contains three sections,

the first of which contains the composer�s melodic

(and perhaps harmonic and rhythmic) ideas for the

piece. The second, development section, attempts to

expand upon, transform, pit ideas against each other

or in other ways deal with the materials given out

in the beginning section. It is not, in some

respects, that different from a musical essay.

Having told us what the composer intends to discuss

in notes and phrases, the composer goes on to

discuss it.

Our reviewer was unhappy that the book gave the

impression that the development section was in fact

not related to the opening section at all. It is

after all much too easy to just string ideas

together without any attempt to make them relate to

each other. Did you see the end of that football

game last night?

Just kidding.

Mr. Reviewer wanted to get things straight,

terminology-wise, but he put his views online, which

means they get equal time with anybody else,

regardless of their manners or knowledge. A couple

of folks rose to the book�s defense. The first tried

to use a specific piece to refute his idea of

sonata-form development in general�Beethoven�s

so-called �Moonlight Sonata� has, he thinks, three

parts which don�t sound related to each other at

all, at least to his ears (it also happens

to be a bad example of textbook sonata form;

Beethoven knew it, too, which is why he labels the

famed �Moonlight Sonata��which was not Beethoven�s

title, by the way--a �Sonata like a fantasy� which

is another way of saying that this is a Sonata that

really behaves like a piece from a completely

different genre, let�s say a science-fiction murder

mystery. Or a fictional historical novel.)

You can tell from the post that English is not this

fellow�s first language. Nor is music. He is polite,

but he thinks that because the 2nd and 3rd

movements sound, in his opinion, completely

different from the first, that makes the first

fellow�s case unfounded. He is confused about what

sonata form is. As I said above, it refers to

different sections within a single piece, or

movement. The different movements are, in effect,

separate pieces of music, which belong in a group,

all under the title Sonata. The first movement is

what usually contains a development section in the

middle. Our reviewer tried to patiently explain

this, and that was when he came under attack from

some jerk who was probably trying to pick a fight by

being as condescending as he knew how and telling

the reviewer that he obviously didn�t know what he

was talking about, using words like �foolish and

pathetic� and �idiot� to describe him. It is not

worth dwelling on his comments, since he used most

of his time to deride his predecessor and none

trying to make the case (except in the grossest

generalizations) that he knew anything of the

subject himself.

Let�s go back to the quote again. The reason I

found this worth posting is the question it brings

up when writing about music for laypeople, or

amateurs.

"The development often sounds like it

belongs in an entirely different piece of music

altogether�"

I�ve italicized those words above because, on

careful inspection, it doesn�t appear that the

book�s authors are necessarily suggesting that there

is no relationship between the opening

section (the exposition) and the development (which,

by definition, develops what came before), just that

it might seem that way. Why would they say

this?

Perhaps in an attempt to be friendly with the

book�s readers. People often do not hear the

connections which musical ideas have with each

other, particularly over long pieces. We aren�t

taught that in school, and it does not seem to

naturally occur to people in music, although in

another medium, say a Seinfeld episode on

television, in which getting the joke depends on

remembering something that happened ten minutes

earlier, people seem to be able to pick up on it

fairly easily. Most people usually listen to music

that doesn�t function on this level because it

simply repeats the same musical ideas again and

again without changing them in any way, therefore

there can be no relationships between various parts

of the piece because they are either identical, or

completely disjointed (like when it is time for the

chorus, which then repeats its phrase several

times). "Popular" music generally assumes you aren�t

interested in connections between musical thoughts;

so-called �classical� music challenges you to find

them. With a little help from your friends, perhaps.

Last months� Music From the Yellow

Room selection, incidentally, was deigned to

do just that. The commentary and sound file examples

there will help your ears pick up on the connection

between various sections in the piece. Perhaps over

time you will develop the ability to understand the

musical narratives of many �difficult� pieces

because your ears have been trained to understand

what to listen for. This is no different than the

fact that you can understand this article because

you can read it, and decode the various words and

word-relationships. You had to learn how. It didn�t

just happen.

But if you are a self-described �dummy,� with a low

opinion of how much you can learn with a little

patient effort over time, or you are an author

anxious not to appear too much of a snob by using

terms like exposition and development, and want to

relax your worried audience by making jokes and

being entertaining, and by not dwelling on

technicalities that perhaps can be saved for later,

you might look at such a line as a good way to

connect, never mind whether it�s accurate. Of

course, the reviewer only quoted this one sentence.

If the book�s authors went on to refine their

statement, explaining that there really is a

relationship between the exposition and the

development (otherwise it wouldn�t be a

�development�) than perhaps our reviewer is being a

bit of a nitpick after all.

The book�s other reviewers were unilaterally lavish

in their praise. Perhaps it is the very thing for

the people who need it: speaking to them where they

are, not shutting the doors to the halls of art or

driving people away with too much technical

precision or jargon. The question, though, is

whether the book is playing too fast and loose with

music as it is, or as it could be, sacrificing

accuracy for entertainment, or truth for simplicity.

I don�t know. The reason I want to bring this up is

not limited to this particular book. Writers on the

arts for lay audiences always come up against this

issue. I often find myself wrestling with the same

problem. This website was not designed for experts,

but for those willing to discover something new. It

(hopefully) doesn�t presume a lot of technical

knowledge. Terms are defined, or left out, and jokes

and generalizations are aplenty. Is that going too

far?

I�ve read several things on the web and in books

that I think do go too far. Trying to draw in the

uninitiated always risks diluting your delivery,

betraying your substance. Does it always? Can we

have it both ways? Can we who know much about art

and we who know very little but are willing to find

out cut each other a little slack? If someone wishes

to correct our statements, should we thank them,

even when we think they are being annoying? Can the

rest of us tolerate a few slips on the parts of

those trying to learn, so long as they don�t fall in

love with their own ignorance and tongue-lash

anybody who tries to help them out of it?

What do you say: truce?

Dialogue with a Steinway

posted September 15, 2009

Sometimes you play the piano. Sometimes the piano

plays you. If you are lucky, maybe there is a little

space in between.

A month ago I went into the recording studio to

visit a 7 foot Steinway. I like to keep those things

company every so often so they don't get lonely.

Steinway makes a nine foot piano which is the

constant companion of every conservatory teaching

studio and concert hall wherever they can afford

them, but the seven foot model will do in a pinch.

Size actually does matter in a piano--more on that

some other time.

When I went in I had some pretty definite ideas

about how I wanted my pieces to sound. I'd planned

my interpretation of each piece, sculpting every

phrase; I like spontaneity, but it is risky because,

either on stage or in a studio, if the muse doesn't

show up, you wind up with a lot of useless notes

milling around with no idea why they belong

together. I figured, 'tis better to plan your

attack, then, when the tracks are recorded once, you

can be spontaneous as the mood strikes in the time

that is left. Spontaneity has value, however,

particularly in conjunction with its close cousin

'adjustment' which is what quickly becomes necessary

when all of your plans go awry.

The first thing I realized about this piano was

that the action was quite a bit different than the

action of the pianos I have been playing recently.

This called for some rapid adaptation since I had

never met this piano before and I wanted to get some

things recorded right away.

This piano had a stiffer action, meaning I was

going to need to use a little more muscle to push

the keys down. Some of my more subtle key strokes

weren't even going to sound if I didn't gauge them

accordingly. On the other hand, the ones that did

make the grade were louder than I had imagined. This

was because we were in a small room with a big

piano. I'd like to say I can adapt to these

situations instantly with no muss or fuss, but that

is overstating the case a little.

Pianists are aware of this problem. You can't take

your piano with you, so unlike the bassoon player,

or the violin player, or the accordion player, or

the guy with the kazoo--practically anybody short of

an organist who makes a musical noise,

actually--part of the game is always adjusting to

the piano that is available on the premises.

Including really bad ones. Or the ones with whom you

personally happen to have a pretty serious

difference of opinion. For example, there are some

pianists who like to have a piano that fights back a

little, and occasionally, but very occasionally, I

number myself among them. Usually I prefer a lighter

action.

One of the most challenging times I've had in this

regard was a time I was accompanying a voice recital

during grad school. We were scheduled to have a

dress rehearsal in the concert hall, as is

customary, but some bureaucratic snafu kept us from

actually getting the chance (which was also

customary). Oh well, I though, I've played a dozen

recitals in that space this year (I was working as a

grad assistant in accompanying at the time) so I can

adjust. When the recital began, and I walked out on

stage and sat down on the bench, I noticed from the

fall board (where the brand name of the piano is

written) that they had gotten a new piano in there,

one which I had not played. I had never seen this

piano before in my life and now it was my job to

strike the first chord of the concert---as softly as

possible. If I misjudged it would be pretty

embarrassing. I took my best guess and, fortunately,

the result was wonderful. So was the rest of the

concert, actually. A good memory!

I have developed a sort of vocabulary of

experiences with pianos over time which helps in

various situations. In this case, I told my

recording engineer that the piano reminded me of a

particular piano in a particular practice room at

the Cleveland Institute of Music. Room L, I seem to

remember. Yes, if I close my eyes I can still

remember the pianos. I spent hours every day

operating them, so why not? Room C was a particular

favorite. Or E. I did not care to get stuck in room

R. Room J required I be in a particular mood for it

to be enjoyable. I could tell you the same thing

about the Peabody Conservatory. If you go there, I

recommend room 243. I spent a very nice afternoon

with the Goldberg Variations once. Of course the

pianos and their actions have probably changed a lot

by now.

But beside the action, there were a few problems to

contend with. One of them was that the una corda

pedal needed some adjustment. This is a pedal that

moves the hammers over very slightly so that instead

of striking three strings for the higher notes, they

will only strike one, making the sound weaker. This

is the grand piano's 'soft pedal.' However, if the

pedal shifts the hammers over too much, they may

strike a string from adjacent notes. This is what is

happening on the recorded example here. I

did not miss that high note--the piano did. However,

once I found out about it, I made sure to play that

passage again, without holding that pedal down. When

I get around to posting that recording you won't

hear the glitch. It only affected a few notes which

is why I discovered it only as I was playing the

piece you just heard part of--about 10 minutes into

the session.

It is curious to discover, while you are recording,

that the piano has planted little landmines for you

to come across every so often. I should mention,

however, one problem that I did not have to adjust

to. The pedal was no problem at all. A couple of

years ago this studio had a nine-foot Baldwin, which

was an alright piano (and in fact recorded better

than it sounded; the strange relation between what

you heard in the studio and what the microphones

thought they heard is another odd part of

the recording process. Some of my least favorite

chords or takes sound pretty good when you hear them

later, and vice versa.). It did, however, have some

wheels (casters) that were a bit large and which

made the pedals a little too high off the ground. We

resolved that situation on the second day by raising

my heels with some kind of mat. But the pedals were

also noisy; I spent some time during editing getting

the pedal noises out of there as creatively as

possible.

In theory the very best pianos will allow one to do

anything with ease and comfort, just as the best

interpretations will immediately size up the

strengths and weaknesses of the individual

instrument and, without apparently sacrificing any

of the substance of the music, play to its

particular advantage. There is nearly always

something to adjust to, especially as the family of

pianos, even the good ones, is so eclectic. The

sustaining power, singing tone, attack, relative

strength of the bass and treble, all can vary

tremendously, and can mean that every note, every

phrase has to take the differing conditions into

account.

This is another sign that music does not exist in a

vacuum. It is always characterized by the time and

place of its birth as well as the personality of its

creator and the limitations of the musical

vocabulary then in existence; melodic, rhythmic,

harmonic, what kinds of symbols were available to

use in writing it down, and what instruments were

available to make it sound. And whenever it is

recreated, the same applies. The understanding of

the player, and the limits of each instrument insure

that it will not sound exactly the same way again,

that no other performance will be precisely the

same. Even in the age of recorded sound I find that

the sound can change radically depending on the

playback equipment. And then there is the mood of

the listener. What will they hear and how will they

hear it? All factors that swirl around this

phenomenon we call music, and keep it ephemeral, and

mortal, and alive. Each moment unique in a

practically infinite chain.

Sort of gives that B-flat a bit more grandeur to

think of it that way, doesn't it?

I'd Like to Thank the Academy...

posted August 18, 2009

I owe some people a thank you. Most of them are too

dead to receive it, but I thought I�d pass it along

anyway. The first is the fellow who came up with the

idea for a piano. His name was Cristofori. In about

1700 he invented a new kind of machine that allowed

the touch of the player to determine the volume of

the tone produced. This was a new thing for a

keyboard instrument. It wasn�t an easy thing to do,

either. Sure, it looks easy. Push a key down and it

the other end goes up and hits a string causing its

little ouch to vibrate at a predetermined pitch. But

if you�ve seen the inside of a piano, you may

have noticed that it is in fact an extremely

complicated process. So complicated that Cristofori

couldn�t think of it all himself. He had plenty of

help. In fact, when you start taking the instrument

apart piece by piece you start to wonder what he

really did invent, anyway.

For one thing, we already had keyboard instruments,

like the organ or the harpsichord, or the

clavichord. In fact, the idea of striking keys to

produce sound goes back to antiquity. All kinds of

neat variations on this scheme were tried, including

one that used waterpower to operate something that

sounded like a pipe organ.

The idea of vibrating strings wasn�t new either.

Besides violins and guitars and musical bows and

arrows (less musical if you are on the receiving

end), the harpsichord already combined the idea of a

keyboard with struck (or in this case plucked)

strings. So Cristofori�s invention didn�t even look

new. It sounded new, though. Bach didn�t like it.

Besides the shock of getting used to the sound and

a new way to play the thing, there were a few �bugs�

in it. It was called the �soft-loud� because that

was the only way they could think to describe its

unique contribution to the genus of musical

instrument, but the marketers kept calling it a new

type of harpsichord because they needed to reference

it to something people knew. It wasn�t uniformly

soft or loud across its register, and the sound was

a little weak, though that wasn�t as much of a

problem as long as it wasn�t asked to fill a large

room. Mostly, it lived in drawing rooms and palaces

for a while. Then they started changing the rules

and asking it to give public concerts. New materials

arrived, like iron, and tougher wooden casings. That

gave the piano a chance to change its stripes.

Over the next century and a half an enormous number

of things were done to the piano. Making the hammers

come to rest so they wouldn�t bounce around after a

heavy attack on the piano. Allowing them a temporary

rest near to the string so the note could be struck

again quickly. Reinforcing the strings in duple or

triplicate so the sound would make it to row

triple-Z. Making piano wire something sturdier so

that that Beethoven guy wouldn�t keep breaking

strings. Creating new kinds of pedals to add

different affects to the sound, most of which, like

so many ideas, died an early death. Building pianos

into loveseats and curving the keyboard are just two

more that didn�t last.

Each of these innovations cost somebody somewhere

years of work trying to figure out the best way to

solve a pianistic problem to improve the instrument.

And some of those improvements were themselves

improved by others following in their wake. The

piano was most definitely created by a committee.

We don�t often think about it, but we are

surrounded by things that people spent their lives

working on�either to invent, or perfect. We don�t

thank them; in many cases, we couldn�t. Their

exchange with us is anonymous, their sometimes

astounding influence on our lives unnoticed. Not

that such innovations are always good. But for their

benefit to humanity we hope they at least got some

recognition, and maybe even got paid for it, which

is humanity's anonymous way of making sure that

people who have something to contribute feel the

love, or at least that, no matter how

self-interested they are, they don�t keep their

thoughts to themselves.

If you need some light summer reading there is a

book called "Men, Women, and Pianos" by Arthur

Loesser which I read some years ago. It is filled

with interesting characters and charts the various

evolutionary additions and dead-ends with respect to

the instrument itself and chronicles the people who

played it. There have been an awful lot of folks who

have shepherded this piano project down through

three centuries, insuring that I�d spend a

disproportionate part of my life seated at a box

that makes noise. I ought to acknowledge them. Some

of the results of this bizarre chain of causation

are on your left, near the top (under the picture of

the hands on the keyboard).

Enjoy!

[Note: those directions in the last paragraph above

made more sense when this article was posted on the

home page, but you can still access the site's

recordings by going here.]

Precedent

posted July 18, 2009

There's been a lot of talk this week, during the

Sotomayor confirmation hearings, about precedent. This is the curious

process by which a court, in deciding a case, checks

to see what other courts and judges have said about

the same or similar issues in the past. Anyone who

is studying to become a lawyer can quote mountains

of legal precedents, and so it is no surprise a

judicial appointee at such a high level (she was a

lawyer once, you know) has had her thinking

practically saturated with them.

I referred to the idea as a curious concept

because, if all you ever do before rendering a

ruling is to go see what everyone else has already

ruled on the matter, your job has pretty much

already been done for you. In this sense, we are

operating under a kind of legal peer pressure in

which nobody wants to do anything that hasn't been

done before. Of course, strictly following precedent

is a luxury even the most conformist judge can't

afford in real life, not the least because if

everybody merely followed precedent (if this were

even possible) then there would be no precedent to

start with. No--Sooner or later somebody slips up

and we get the sense that we are working with a live

person with their own opinion, whether it has been

'informed' by precedent or not.

In Ms. Sotomayor's case it is wise to use the issue

of precedent as a kind of cover. If you don't want

to make waves you'll be sure to be able to say that

you were just doing what everybody wanted you to do,

or had already done. You'll assure people that you

are hardly acting on your own in any discernible

way, and that you are a responsible part of the

system whose own particular biases cannot be pinned

down.

If, on the other hand, you want to gain attention,

the best way to do it is buck precedent. People will

love you, or they'll hate you, in large quantities

all around, but your visibility will command

attention. I bring all this up because we have the

same thing in music. Art music, anyway.

This is because it has a long history. Whenever

there is a long history, people have the privilege

of arguing about what that history is. Or ignoring

it. At one time musicians were less 'burdened' with

a vast past repertoire, but those days are gone.

These days the wind blows in the direction of

something known as the authenticity movement, and

musicians who are performing music of past eras are

expected to render their interpretations in

conformity to what a vast network of musicologists

and educated performers believes to be the manner in

which said work would likely have been performed or

interpreted by the composer.

This is not the same thing as tradition, which may

have grown up independently of any reference to past

styles or scholastically informed approach, or have

its roots in a time when people where more concerned

with getting those problematic works of the past to

sound more 'up-to-date.' Too bad Bach didn't have a

300-piece orchestra. Well, he does now! Thanks to

Wagner and Strauss who arrived on the scene a

century later we have these massive orchestras with

a hundred brass players in them and we don't want

them to feel left out when we do a little Bach, so

we'll 'improve' the old master. We're sure he would

have wanted it that way. This sort of orgy of late

19th century practice--rewriting the performance

styles of any other historical period in terms of

the here and now had its heydey in the early 20th

century, and has pretty much died off under the

withering glare of academic research and opinion.

It's not as if everyone agrees with those

assessments, however. There is plenty of debate

about what constitutes historically accurate

performance, and whether it is fair to assume that a

composer would have passed up the chance to

incorporate some more recent innovations in his

performances. And that's where tradition, i.e.

precedent, gets interesting. Just like in politics,

there are people fighting over the proper way to

interpret certain composers and styles, influencing

one another in an attempt to gain the majority. Once

a powerful and influential performance hits the

market, it often becomes precedent. There is a power

in that, and with a species that values herdthink,

genuine risk in bucking that tradition, however it

got there. But people do it, and they are usually

the ones who end up getting the most press. Whether

they are playing the music like they honestly feel

it ought to be played or exercising their egos (or

some combination), it is those players who end up

setting precedent by being bold and different.

Either that or the musical public and practitioners

figure they are out to lunch and they don't make it

into the record at all.

When I was a conservatory student I was often a

captive of precedent. Sometimes my interpretation

would be called into question because it could be

shown I was violating the intention of the composer.

If Beethoven put a crescendo beginning on the third

beat and I begin to get louder on the second, I was

just wrong. Any professor would have pointed out to

me that Beethoven was a smart guy who knew what he

was doing and exactly what he wanted to a T. He had

authority--ultimate authority. But in a situation

where there were no markings--say the tempo of a

piece by Bach, or the articulation or phrasing--none

of which was displayed on the page, I was also

sometimes given to know that I was simply in the

wrong. Often my professors did not feel the need to

explain themselves; sometimes I did not push the

issue. But I often felt that I was violating

precedent. The current way to play a certain piece

by Bach was different than the way I was approaching

it. Some strong personality somewhere had set a

trend and gotten lots of other folks to agree with

it, whether that was based on the latest research,

or a convincing sales job by an attractive

personality, or seemed to answer an unconscious need

in our collective psyche. It might have also been

the professor's personal opinion, but if you've been

at a conservatory you understand that there are

certain norms that even the professors get in

trouble for violating. If you want respect, you

don't go out on your own. You honor the past, which

is why a conservatory is so aptly named.

I think it was famed conductor Arturo Toscanini who

said "tradition is nothing but the last bad

performance." It seems safe to assume he wasn't

interested in what everyone else thought you were

supposed to do with a Beethoven symphony.

This seems to be where music and politics diverge,

when a strong, charismatic figure decides to do

things his way without caring what others think. It

seems that way, anyway. But often, that individual

is also appealing to precedent--if not to

tradition, which may be as recent as yesterday or

storied in the past, it is The Composer's Authority.

That's because, like our political system, the

assumption in art music is still very much that the

composer is the final authority. One way to buck

precedent without getting in as much hot water over

it is to appeal to originalism, which is precedent

raised to the third power. Bypassing the traditions

that have 'corrupted' the original intent of the

composer, the performer seeks to 'restore' (with or

without the aid of a committee of historically

informed musicologists) the true and proper way to

approach the piece. On the supreme court, justices

argue about who is realizing the intent of the

founding fathers most accurately. But no one says

they aren't interested in what the founding fathers

think about the issue. They may find creative ways

to justify what seem to be new interpretations, but

justify it they do. And they accuse their opponents

of being false to this tradition.

Much like the way harpsichordist Wanda Landowska

settled an argument by telling a rival, "You play

Bach your way, dear, and I'll pay Bach his

way."

Precedent is a strange dance. There wouldn't be any

precedent if somebody didn't create it in the first

place. Once they do, it becomes a recognized

authority in the age old attempt to check innovation

by making it stand trial against its ancestry. Once

it has been hallowed by time, its creators either

develop reputations that can't be touched (what, are

you going to try to tell me Washington was wrong?)

or they are forgotten, and become that time honored,

"they say..." and you know what they say...

Well, whatever it is, you'd better listen.

An Exercise in Creative Ignorance

posted July 1, 2009

I�ve been seeing them everywhere for years, so the

cartoon strip this morning that featured some of

them did not really surprise me. Here is a sample of

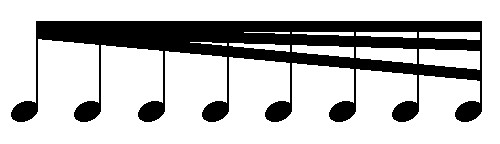

what I mean:

Now, a musician can tell by looking at them, that

there is a small problem with these notes. And the

small problem is that they are illegal. They don�t

exist. There are no such notes that look like this.

They are imposters.

But they do look sort of cute, don�t they? I mean,

if you are not a musician, they do sort of look like

they might be the real thing. Musical notes have

circular heads with sticks attached, and those funny

lines to join them together sometimes. And sometimes

the head parts are filled in with black and

sometimes they aren�t. So why not have some of those

notes with the beams not be filled in?

It seems like it could work, except that it

doesn�t. This is much the same, I imagine, as if

somebody tried to invent a letter of the alphabet

with various curves and lines in appropriate places

and came up with something that wasn�t one of the

current 26, or an Arabic number that looked kind of

like a 3 married to a 6 with a little 2 thrown in

but wasn�t anything you could add with.

The obvious reason for this, of course, is that

persons like the cartoonist, or makers of all manner

of musical kitsch I�ve gotten as presents over the

years filled with these impossible notes, is that

the people drawing them have no idea about what they

are drawing, and it looks ok to them, so why not?

This sort of thing can be particularly amusing if

you are watching a movie where the actor is trying

to play the piano and is, let�s say, unaware which

end of the piano has the high notes, so he is

�playing� the wrong end of the piano as the

soundtrack music is gushing forth. Sometimes the

finger strikes are simply out of sync with the

music, or there is a completely exaggerated bouncing

around on the part of the fake pianist--maybe the

music is smooth and he looks like he is banging away

at heavy chords. One cartoon I saw had a violinist

holding the bow completely still on the string for

all the long notes and only moving when the player

changed from note to note. This is a physically

impossible way to play a violin since you can�t get

sound from a vibrating string without actually

moving it across the string the whole time you want

it to sound. As it happens, you don�t need to change

the bow direction at all when you want a new

note�only the fingering in your other hand.

Watching pretend musicians fake it on film can be

quite funny�or exasperating. Occasionally, somebody

either knows how to play or has taken the trouble to

observe people do it and is able to give a

convincing con. But not usually. And in the world of

throw-pillows and musical stationary, I don�t think

I�ve ever seen a line of music that didn�t contain a

few errors.

The favorite, of course, being the unfilled-in

eighth or sixteenth note, which is sort of a musical

hybrid, like a griffin or a centaur. Since notes

that aren�t filled in all come from the slower or

longer-lasting end of the time-scale, and notes

which hang around in groups and are beamed together

are the shorter or faster ones, this is the musical

equivalent of stitching the head of a turtle on the

body of a cheetah.

Now I could complain about this for a while, but in

these democratically vibrant times, it is considered

mean-spirited to call ignorance to account, rather

than join in its merrier attitude, and besides, part

of creativity resides in ignoring, willfully or

unknowingly, previous rules or customs to foster the

creation of something new. So what I have in mind is

to find a way to 'legitimize' these new notes so

that musicians can use what the blanket and

paperweight makers have already shown us. It will be

a challenge for the musical establishment to accept

this, but less of one than getting people who can�t

be bothered to just copy some actual music into

their designs to learn some rules. Besides, it will

be fun. So here goes:

Right away I can think of three questions. What do

we call the new note or notes, how does it/do they

function, and what official body can we get to

recognize our new creation(s)? I�ve worded the

question in the plural because it looks like we may

have to name at least two kinds of notes: the

unfilled-in eighth and unfilled-in sixteenth (both

beamed and flagged). Perhaps while we are at it we

should add versions of the 32nd, 64th,

and 128th notes as well.

Now to the name. Most of these notes are named

after fractions (and tend to be halves of each

other). You�ll note that only a few of them are

taken. There is no such thing as a sixth note or a

nineteenth note, though those names aren�t very

catchy and probably come from those boring old guys

from antiquity who thought everything in the

universe was an expression of math. So while there

are plenty of numerical names left, we don�t want to

miss our chance to call them things like �Fred� or

�Bert.� Or, now that mathematics has moved on from

Pathagorous, we could celebrate its complexity by

naming one of our notes after the Euler number, or

the Arc-Tangent of the angle of the beam or

something special like that.

The function of the note is where we really have

problems. Not that the 20th century was

any stranger to new musical symbols. Usually they

were suggested by the composers themselves to cover

musical pheonemena that couldn�t be called forth

using the symbols they already had. For instance,

this:

means to gradually play the notes faster (not

suddenly to go from one kind of note to another

twice as fast--this rather rigid series of 2:1

ratios is how the progression of traditional

note-values developed). One reason this sort of

thing works is because it is a combination of a

crescendo, which means gradually get

louder, and is represented by two lines diverging,

creating more space for the expanded volume of the

music (visually representing the concept!), and the

traditional idea that the more beams you have, the

faster the note value. A sign like this makes

intuitive sense. Plus, the composers would explain

what the new signs meant in a preface to the musical

score so as not to confuse anybody.

Since as I�ve already explained, we have here two

pieces of musical information that seem to

contradict each other�a �slow� note-head and a

�fast� beam�I'm really flummoxed as to what to do

with this one. Could it mean to sustain one member

of a group of fast notes (though we can already

represent that with double-stemming or pedaling

instructions) or to emphasize it (but we have

accents for that)? Email me if you get any good

ideas ([email protected]).

Finally, if we want the note to have any kind of

shelf-life, we�ll want to get it sanctioned by

somebody with some musical authority. I�ve recently

taken it into my head to see whether there is a

musical equivalent to the Chicago Manual of Style

and have not had any luck so far. As a composer and

teacher, I�ve noticed that a lot of the �rules� we

were taught when young mask a lot of diversity or

practice that goes unnoticed by music teachers and

publications. I suggest that if we got our notes

into an upcoming version of the Groves Dictionary of

Music and Musicians, or the Harvard Dictionary of

Music, we would be making some good progress. We

will then want to trumpet our new symbols with all

the fanfare that astronomers lavish on the finding

of a new planet. It will be big news for a day or

two throughout the land.

There may be those rare instances when someone

trying to fake musical notes has not already

stumbled onto our discovery. Cartoonist Charles

Schulz, creator of Peanuts, used to use actual

snippets of Beethoven Sonatas in his panels. They

might have been missing clef signs or time

signatures or have started mid-measure, but the

notes were right, stem directions and everything,

and it was fun to figure out which piece he was

quoting from. I�ve heard some suggest that he even

chose particular pieces as a kind of comment on that

strip.

I don�t know if we�ll find anyone that care-ful

again. Meanwhile, we can, like heartless pedants,

mourn the laziness and lack of knowledge of the

world around us, or we can use that ignorance as a

spur to great deeds of creativity, and look upon it

as a gift. And the best part is, it keeps on giving.

older posts

|