|

How Not

to Write a Musical

Some years ago, I had the

misfortune to offer my services to a lady who had

written a musical. This had apparently been her hobby

for some years, and it would have been a perfectly

harmless pastime except that she wanted it to be

performed, which meant that there were going to be

musicians involved who would have to decode her

instructions and somehow bring this voluminous

enterprise to life. I seem to recall she was in her

eighties, and had spent most of her life writing what

she called her 'baby.' She therefore did not seem

interesting in hearing any suggestions, most of which

were of a purely technical variety on my part, though

if I had been honest I would have suggested quite a

bit of rewriting as well. The musical had at

least been printed on a popular computer scoring

program so it was legible, but there were so many

things that made it awkward and nearly impossible to

execute (not because it was hard to play but because

so much of it did not make sense; the musical

equivalent of spelling errors and poor syntax

throughout made for very rough sledding). In a

few cases during rehearsals, when trying to deal with

several of these problems at once made me ready to

spit nails, I tried very politely to explain a few of

these concepts to her, but they did not take root for

whatever reason, and, since I did not want to crush

her ego, I kept quiet about most of it. Eventually,

after struggling over the issue, I decided that

nothing useful would come from offering to help her

"revise" her score, (which I'm sure she didn't think

was in any way necessary) but the teacher in me would

still like to do whatever is possible to prevent

something like this from happening to anyone else who

would like to avoid it.

Therefore, consider this

the Marley's ghost of compositional advice--please, for

the love of Pete, if you are writing something that you

want people to perform, consider the following items.

They are not here to ruin your inspiration, merely to

keep the musicians around you from losing their sanity.

Most of them seem like common sense. However, when you

are writing a large and complex musical work, there are

an astonishing number of things that you can do wrong.

Since this lady did practically all of them, I have it

in my power to warn you against making the same

mistakes.

There are many people who

have the quaint idea that a composer is someone who

works in solitude on in a mountain villa by an open

window, blissfully being bombarded with musical ideas

like neutrinos and simply writing them down without any

need for second-guessing anything. No technical

knowledge is required; anything learned can only get in

the way of a good inspiration. These people's patron

saint is Mozart, who may have actually come the closest

to really composing in this manner, except for the small

fact that he had a teacher-composer father who gave

young Mozart all kinds of technical instruction from the

age of three, and who took Mozart all over Europe,

admittedly showing him off before astonished royalty

(astonishing royalty is not as hard to do as you might

think), but also giving Mozart exposure to the best

minds on the continent so that before he was very old he

knew a lot of stuff about music. This, and the fact

that, while many of his papers were destroyed, there are

also plenty of sketches and unfinished compositions that

show that Mozart didn't just take dictation from heaven

and never change his mind about anything. He learned, he

tried, he failed, he assimilated, he thought about how

to write music constantly.

Now, the history of music

is also filled with narrow-minded pedants who liked to

tell composers that their most audacious and

ground-breaking ideas simply would not do at all, and

like to pour cold water on their best inspirations. But

every undergraduate theory student who gets his or her

compositional assignment corrected by a teacher is

liable to put themselves in such a grandiose position

too, so you see how that philosophy can be taken too

far.

Basically, anybody who

really wants to be a composer ought to get some kind of

training; you can always decide later which advice to

heed and which to ignore. Just because you know how to

do something doesn't mean you have to do it that way,

but not knowing in the first place means you are greatly

limited; for example to the three chords that this lady

was using. If she had known how to use them properly she

might have kept us entertained. There is, after all,

some charm in simplicity. But then, there is what I call

simplicity by choice and simplicity by default. The

first kind is some of the most beautiful music in the

world. When a great genius in music, who could write a

lengthy 6-voice fugue chooses instead to write a simple

melody, the effect is often astonishing. But the second

kind of simplicity is asking for trouble--when a chord

or a turn of phrase is the only one the composer has in

his or her imagination, even though it doesn't fit very

well. Maybe some of your notes don't get along with the

others.

It is not necessary to

obtain a license to compose music--most means of

expression, artistic or otherwise, are about as

unregulated as the food supplements industry. And since

you are entitled to "lose 50 lbs fast!" simply by

swallowing some tasty pills, you might as well be

entitled to command certain sounds to arrange themselves

in a certain order without bothering yourself about

whether there is a better or worse way to do it.

It is inspiration, after all. Which, when you think

about it, is a lot like opinions. You can arrive at them

however you like.

There are, in the course

of any kind of composition, any number of decisions in

which judgment and taste play a role. But most of the

suggestions below are of a purely practical nature. It

generally does not mess with a novelist's artistic

vision if his publisher numbers the pages. Most people

consider it helpful to be able to find page 336 when

they want to. It is the same in music.

I'll begin with the most

technical, detailed explanation and work outward. You

can skip it if you are not in the mood for music theory

right at the moment.

First of all, listen to your

performers. If they are having trouble singing something

you have written, it might be because they are poor

singers; on the other hand, perhaps what you have

written is awkward. If they are forever instinctively

changing one note, that may be because the phrase is

much smoother that way. Let me submit the following for

your consideration:

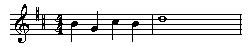

The first phrase

represents how everyone is singing your tune; the second

is how it was written. However, the second way contains

a few problems. The first is that there is an odd

interval called a

tri-tone between the second and third note, which is

hard to sing. Not impossible--it can even be used

effectively, for example in Bernstein's West Side Story

when Tony sings of his new found love Maria on these

notes:

The tri-tone was once

called "the devil in music" which I take as a sign that

early music theorists didn't care for it a lot.

Just to show why

things like these take a bit of discussion with a

person who knows what they are talking about--Your

first

phrase has the same three notes at the beginning, and

the matter turns out very differently. This is because

what is really going on here is that we are singing

two things at once, known as a "compound line." The

first and third notes are leading us up to the final

note, the

door prize

(disclaimer: not an actual musical term), and the

second and fourth are as well. Well, sort of. What the

second line needs to do, not-obviously-enough, is

establish the "dominant" harmony, which is always five

notes up from the key of the piece, in this case D.

That would make our dominant pitch an A. This dominant

harmony functions as a kind of harmonic glue to get us

to our "door prize" harmony. You've heard this formula

millions of times in your lifetime whether you know it

or not. It became, for about 300 years,

the

harmonic pattern our ears were itching to hear. Three

centuries is a pretty long time for a fad, if indeed

that is all it was. And we're still not over it.

Interestingly enough, this

dominant harmony, in the key of D Major, contains the

notes A, C# and E. C# is particularly important because

it is the tone that leads the ear the conclude on the

note D. But in the first example, the C# doesn't go

where it ought to. It is false advertising. It goes in

the wrong direction, and it suggests the wrong harmony.

This is not a good time to introduce a note belonging to

a sub-dominant chord; if you wrote an essay for English

class in which you discussed the need for aid to Africa,

and in the last paragraph decided to talk about the

Cubs' game last night, your teacher would not think this

was a stroke of brilliance on your part. True, there was

a musical phenomena, called a "Landini cadence" in which

the leading tone always gave way to the very same

extraneous note we've got going on above, before

concluding on the keynote, which is guaranteed to drive

the modern ear mad, but that went out of style about 700

years ago.

Then why does it work if

it goes down to an A instead of a B? Because the harmony

doesn't change. Since it is still part of the dominant

harmony, the ear hears two complimentary things going on

here, instead of one unfocused, disjointed thing.

Most singers could

probably not explain this phenomenon, but, at our

rehearsals, I noticed that they all changed the note B

to an A instinctively, which shows you how sometimes a

technical explanation can be avoided if your ear knows

what to do. What is interesting about the two

examples is that, while they both contain tri-tones, the

second version makes it obvious, whereas in the first,

you don't notice. If I furnished the left hand, you

would also notice a nasty disagreement between the

harmony and the melody. What is also interesting is that

everybody in that room seemed to know what was musically

natural except the composer!

Being able to explain why

something works in words and concepts helps in ways

that, alas, might take some explanation. Some people are

quite against any explaining, and if they really can

manage the same results purely by instinct they have my

blessing. But it is rare that a good composer did not

consider that his work involved craftsmanship, and it is

just as rare for the people who have no idea how to make

music themselves to think that it does.

If the above explanation

does not make any sense to you, you may wish to learn

some basic music theory. If you cannot honestly hear any

difference in the two examples above, you might think

about something besides composing, unless you are really

innovative and plan to avoid traditional harmony

altogether.

It is amazing how one note can make

such a difference. Since I have spent so much time

dissecting the matter, I'll spare you the hundreds of

other examples in this musical, which were considerably

more egregious, and could not have been fixed simply be

changing one note. When Peter Schaffer, in the movie

"Amadeus" has Salieri exclaim admiringly "Change one

note [of Mozart's] and the piece is diminished." he

isn't just blowing smoke. This is probably the kind of

thing the kept Chopin up nights.

There are standard rules

that people generally follow when they are writing

words. One is being able to spell them properly. There

is an agreed upon spelling of most words (maybe two). If

you don't feel bound to this you may cause people

reading your work to spend more time trying to decode

your writing then they would like. There are similar

rules in music.

Technically an A-flat and

a G-sharp are the same note--at least on a piano (a

string player may have other ideas). This gives rise to

what we call enharmonic spellings, the choice of whether

to refer a the note between the G and the A as A-flat or

G-sharp, for example. Just like in English, we can't

spell everything however we feel like it, even if it

technically works. For instance, even though the "gh" is

silent in the word light, that doesn't give you license

to spell everything with a silent gh in the middle.

There are similar rules regarding how to spell chords

and melodies, and they are largely based on the function

those notes have in the overall context. If you

are in the key of A-minor, for example, and you choose

to write every leading-tone as an A-flat, you will drive

your pianist up a wall. He will be expecting that A-flat

to lead down to a G natural in the next measure, rather

than up to the A (which is what makes something a

leading tone--it leads the ear up to the key note--here

the note A). Twelve pages of this can make your pianist

very cranky. It is not impossible to read music written

this way, it just takes a lot more painstaking effort,

with no hints as to the music's overall construction.

knot beeing abull 2 speghl

propirlee leeds two alll kiends uv airers thatgh wil mac

yor pees vairy hrd too reid?

There was a point where

the harmony in this musical was so weird I had no idea

which notes to assume were misprints because the

composer's grasp of standard rules of this sort

(including which key signatures to use when) was so

sketchy I could not deduce what the outline of the

musical thought was. Key-signatures also have standard

spellings, and they point out the overall plan and

tendencies of the notes to go in various directions; in

other words governing the behavior of the notes, priming

our ears for what is typically expected and what is a

surprise. A surprise is very difficult to carry off

unless there is some kind of expectation. These key

signatures are part of an overall system and are not as

complicated as multiplication tables; elementary school

students could learn them all, if music teachers would

make the attempt.

The remaining points all

deal with practical matters related to performance.

If you are determined to

make an effect, you will naturally want to employ a

small orchestra. The first thing you can do for their

conductor is not to hide them somewhere that it is

impossible to see the stage and the singers. Every

amateur I've worked with in a musical is convinced that

singers do not need to see the conductor, because in

movies the music just comes out of nowhere and is

perfectly attuned to when the singer opens her mouth. In

the theater there is a guy in the pit, hidden away as

usual, because nobody wants to imagine that there is any

calculated effort involved in the magic of the theater,

but visible to the singers and the instrumentalists. He

is there because 20 people with their own opinion about

when the piece ought to begin is not a great idea. Try

getting 20 people to agree on what to have on their

pizza and you'll see what I mean. That conductor has to

coordinate everything--he literally makes the beat

visible to everyone, so that they can see exactly when

it is time to begin, where the next beat follows, and

how to play a particular passage by whether his motions

are fluid or vehement. Therefore, it is helpful if you

do not position your orchestra so that it is impossible

for the singers to see your conductor. That is not why

large pillars were created.

The next thing you can do

for your conductor is to give him a score. The

"full-score" is a copy of the music in which you can see

what all the instruments are playing. It is organized so

that all of the instrumental lines are joined together

and, though it is written left to right, a single line

of music may be as tall as the page itself, if there are

enough instruments all playing that line together, each

on its own "staff." Since one of the functions of the

conductor is to "cue" each instrument when it is time

for them to resume playing after a break (for security

reasons, partly, since the clarinetist should be able to

keep his own place) it would be helpful if the conductor

knew when the clarinet was actually supposed to begin

playing.

Another thing that is just

a bit helpful at rehearsals is to number your measures.

If the conductor asks you to do this several times, take

him seriously. What he is trying to avoid is the

situation wherein the aforementioned clarinetist appears

to have come in too early and is obviously in the wrong

spot in the music. If this happens, oh, I don't, know,

let's say five minutes into a seven minute piece, the

options are as follows: go back to the very beginning of

the piece and start over, confident in the knowledge

that, five minutes later, the same thing will happen,

probably because the clarinet part has been written

incorrectly (i.e., the wrong number of measures of rest

has been given), or, tell everybody to start at measure

310, which is only a few measures before the problem

spot occurred, so you can fix the problem in a

reasonable amount of time. If you had a full score, with

numbered measures, you would know what was supposed to

be going on--otherwise you will simply have to rely on

your ear and your intuition.

Now, as it happens, most

music writing software programs, like Finale,

automatically number measures. It seems you would have

to intentionally turn them off. This would be an

indication of unfathomably poor judgment.

If you are writing for

instruments, it is not necessary that they should all be

playing all the time. Judicious use of them is a

hallmark of good orchestration. This does not mean that

the best thing to do is to save the instruments until

you have reached the spot where the tempo is about to

change radically, and the singers, having arrived at a

rapturous climax, are preparing to make the audience's

dreary lives worthwhile by hanging out on a high C while

those of a less operatic inclination use this time to go

out and feed the meter without missing anything. When

the tempo is being altered and the opportunity is

therefore much greater for a sloppy and glorious

train-wreck of instrumental imprecision, by all means,

throw every instrument you have into the mix, the better

to cover up the singers, and make certain that none but

the most stalwart tenor will bother with that high C

ever again. Once the music has resumed its normal,

predictable pace, you can let the piano navigate these

boring passages on its own. This way, you don't have to

write nearly as many notes.

|