Looks aren't Everything...unless you are a

Celebrity

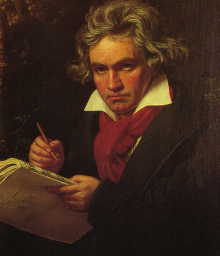

What did Beethoven Really look like?

You've no doubt seen that "official" portrait of

Beethoven--quite serious, defiant, his eyes

blazing thunderbolts to the heavens, his unruly

shock of hair unkempt and wild, refusing to bow

to mere conventions us poor mortals use, or a

comb.

Is

that the real Beethoven? After all,

he lived in the days before flash

photography, and portrait painters could

stretch the truth a little, and they often

did, if their subject was rich, and ugly.

The truth is a bit complicated,

as usual, but it should be noted that well

before he died in March of 1827 Beethoven had

achieved celebrity status. People were

selling his portrait all over Europe.

|

|

|

Ah, yes...then as now people

wanted to be able to see their idols. And

what they apparently wanted to see, more than

anything else, were the ideals he seemed to

represent. Not a mere man.

A

mere man is how the astonished music critic

Ludwig Rellstab described him upon meeting

him in 1825. Though surprised that

Beethoven appeared to him so ordinary, he

had to ask himself "why should Beethoven's features

look like his scores?"

|

|

Of

the hundreds of works Beethoven composed, so

many seem to reflect a man with a sense of

humor, genial, affable, full of joy, relaxed,

and yes, by turns quite serious and profound,

particularly as he aged and his deafness shut

him off from society. And yet his works are

mostly described by his contemporaries as

bold, defiant, shocking, heavenstorming--as

some of them even seem today. But perhaps that

judgment is skewed by an over attention to a

relatively small number of his profoundest and

his most revolutionary works. |

| Beethoven was

born only six years before the American

Revolution and nineteen years before the French.

All of Europe was in ferment, shedding a system

of aristocratic government, replacing the

authority of the nobility with the powerful

economic clout of a rising middle class.

Democratic ideals were in the air. Beethoven

himself wholeheartedly subscribed to that,

believing that Napoleon had come to liberate

Europe. On arriving in Vienna, Napoleon's forces

bombed the city heavily, and a shaken Beethoven

changed his mind. |

| Beethoven was not so lofty

that he was above wanting things both ways. The

old order had placed accident of birth before

personal merit and denied any chance at upward

mobility. But Beethoven was not particularly

concerned when people incorrectly substituted

"von" for "van" and called him Ludwig "von"

Beethoven. While the term "van" is a regular

peasant prefix, "von" signifies nobility. Later

in life, trying to win custody of his nephew

Carl, Beethoven tried to use his "von"

designation to push his weight around. He was

embarrassed when the court discovered this to be

a ruse. |

|

|

Beethoven moved easily in aristocratic circles

and was often patronized by its members. He

dedicated his works to them in return.

But Beethoven did not consider himself

subservient to any of them. One of his famous

diatribes is a rebuke to a prince in which he

shouts that there are hundred of princes

(there were) "but only one

Beethoven!" It is also said that

Beethoven refused to pay any respect to a

party of aristocrats near Teplitz (see the

above painting), while his walking companion,

the famous poet Goethe, stood at the side of

the road with his hat off. The source

for this tale is Beethoven himself, in a

letter dated August 14th 1812 to Bettina von

Arnim. The problem is that the letter may not

be authentic. Ms. von Arnim became quite

famous for her publications of letters from

both Goethe and Beethoven but does not seem to

have been above making history more

interesting than it originally was. Still,

many take the incident for historical fact

(and some date the incident from July rather

than August so that it actually occurred

during Beethoven's visit to Goethe and not a

month later when none of the parties involved

were in town!), and it does seem to illustrate

something fundamental about the character of

each (particularly the character we think we

know). So, did it happen? It might have--or at

least, we want it to have happened. Enough

then. It did!

If Beethoven's uncompromising

behavior was what most drew the attention of the

Viennese, it would be no surprise if the

Beethoven they saw in pictures began somehow to

resemble a defiant revolutionary. But

Beethoven's appearance, at least at first,

remained stubbornly unremarkable.

|

|

|

|

To begin with, his face

apparently had a few scars and deformities, the

results of a possible struggle with smallpox or

some other infectious disease which left a

lingering signature. Though testimony to this

facial misfortune is given repeatedly in print,

it is consistently "edited out" when his

portrait is painted.

The nose,

apparently, was revised as well, being a bit

larger than is commonly represented. The

biggest problem, however, seems to have been

with the eyes, which are often depicted as

gazing heavenward, steely, fiery. More often

in his portrait sittings he was probably

distracted. He hated to sit for them very

long, and, as there came a steady stream of

persons wanting him to sit for them, he

adopted a regimen of inviting them into his

study and then ignoring them, improvising at

the piano for hours and forgetting that they

were there. One of his favorite painters was a

man named Klober who came in unannounced, left

unannounced, said not a word, and simply went

on with his work while Beethoven worked. Like

a good naturalist observing Beethoven in the

wild he must have had to imagine something of

the character Beethoven's features would

assume had he been paying attention to the

proceedings.

|

|

Beethoven himself had favorite portraits. At one

point in his life it was the one on the right.

It apparently does capture much of Beethoven's

actual face, and was thought to be particularly

lifelike by Beethoven's inner circle. It begins

to show us the growing dominance of Beethoven's

favorite feature--his hair. Thick, massive,

unruly, like a lion's mane, this storm-tossed

foliage soon conspired with the furrowed brow

and the intensely concentrated eyes to give us

the Beethoven we know. |

|

|

Because so many portraits of Beethoven were

copies of other portraits it was no great

difficulty at the time of his death for one or

two official versions to gain preeminence.

Helping this cause were Beethoven's close

allies, particularly a man named Schindler who

was so proud of his association with Beethoven

that he had the words "Friend of Beethoven"

engraved on his business card. Schindler went to

great lengths in writing to praise certain

portraits and condemn others, testifying as an

authority since, after all, he was an

eyewitness. |

|

Schindler could have been a reputable source for

much Beethoven lore, but to suggest that he had

an agenda would probably be a severe

understatement. What is particularly interesting

is that he even overrules Beethoven on some

points. Of the portrait above, the one that

Beethoven liked "because of the way the hair was

done," Schindler exclaims that "Of all the poor

likenesses of our master, this one must be

considered the most plebian." But he was able to

share the wealth when it came to unkind words.

Regarding the portrait on the left, by one

Joseph Mahler, Schindler simply writes that it

was not worth making a copy because it was

"mediocre." Beethoven had thought enough of it

to write to the artist, who had borrowed it,

asking him to return it soon so that he could

give it to a young lady, hoping to procure

certain favors thereby. |

|

Beethoven

does seem to have had a weakness for having

his portraits done, though he could hardly sit

still long enough for his artists to capture

more than a quick impression, and if they were

so impertinent to ask more than he would

give--well, they might have to finish the

portrait from memory! The unfortunate

Waldmuller dared to ask Beethoven to sit

facing an open window--a natural light

source-- and received condemnation from the

master. But then, Beethoven was less than

pleased with his face. Nor was he altogether

happy about the talents of some of his

painters, though he wrote "I cannot take

responsibility...for the misfortune to have

made a bad drawing of me" protesting at the same time that

his face was "not really that significant." It

could not have been easy being an icon

throughout Europe; "great is his horror of being

anything like exhibited" writes an

observer. Even after his death careful

attention was paid to capturing for all time his

study the way it looked at the time of his

death, as well as his face and his hands,

quickly sketched, while his ears were removed

and sent away to determine the cause of his

deafness. Copies of his final portrait

were immediately sold throughout Europe.

|

|

This

essay owes a great deal to Alessandra

Comini's very interesting book, The Changing

image of

Beethoven: A study in

Mythmaking (1987, N.Y.: Rizzoli)

particularly the first chapter. All of the

above pictures appear in this book, and all

are portraits of Beethoven! (in case you

wondered). The blatant opinions, however,

are mainly my own. |

|