|

One

enduring idea that people often have about

artists is that genius and insanity are

closely linked. It seems like a pretty

self-serving idea, which may account for its

popularity. After all, if people who are

geniuses, and therefore far above the ordinary

orbits of regular folk, are also more than a

little crazy, which is something to which no

one aspires, than at the very least things

come out even. More likely, if a wish-granting

genii could make you a genius but would also

have to make you insane, you could be pardoned

for saying �no thanks!� and preferring to

remain just an ordinary, perfectly

respectable, sane, societally-sanctioned human

being. Now

don�t you feel better about not taking those

piano lessons? No telling where they were

going to lead.

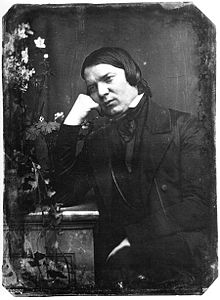

On

the other hand, the myth�s popularity might

have a simpler explanation. People tend to

remember the sensational, not the ordinary.

There have been great gobs of great artists

with perfectly ordinary lives, who at best

seem a little eccentric to their

contemporaries, but who do not attempt suicide

by throwing themselves into rivers, wind up in

insane asylums, and dying there. And then

there is Robert Schumann. Or was.

|

Because he

lived in the 19th century, when medical

diagnoses were often pretty vague, musicologists get

to speculate on what exactly was going on in

Schumann�s mind and body. But he exhibited the

symptoms of a manic depressive, going through periods

of wild exuberance involving great spurts of

creativity�he sketched his first symphony in three

days�and then periods of several melancholy and

depression.

The

fragmentation of Schumann�s mood is reflected in his

own imaginative experience. A frequent writer on

music, with opinions to spare on composers of

performers of the day, Schumann founded a journal and

poured forth review after review. In a famous review

about Chopin, he introduced Florestan and Eusebius,

two distinct sides of his personality. Eusebius, the

poet, reflective and dreamy, and Florestan, the

passionate, exuberant, easily enthusiastic self. Both

of them received musical portraits in Schumann�s piano

cycle �Carnaval� in which figures from Commedia

dell'arte mingle with real persons from Schumann�s own

inner circle.

Schumann�s

liking for the edge is evident in several of his

musical instructions. Some simply require really

bizarre dynamics, where the accompaniment is

intentionally much louder than the melody. Then there

is the famous set of markings on his second piano

sonata, �as fast as possible� followed a page later by

�faster!�

Obviously

the ordinary didn�t appeal to Schumann. He lived in an

age when men were supposed to show strong emotion, and

to weep was a sign of a sensitive and powerful soul.

Dramatic dynamic contrasts abounded, and the climax

was always hair-raising. Composers were often writers,

and philosophers, and had strong ideas about the role

of their art. Before them, the romantic poets had

paved the way, and one of the best-selling books of

the age involved a suicidal young poet.

Schumann�s

life was dramatic enough. Shunted off to law school at

his parent�s insistence, young Robert simply couldn�t

apply himself, and quit. He took piano lessons with a

virtuoso teacher who was training his daughter to

light up the pianistic sky. Robert fell in love with

her; the father-in-law refused his blessing on the

union. Clara was too young anyway, but Robert sued to

marry. It was a protracted battle that the young

couple eventually won. Meanwhile, Robert has ruined

his right hand using a device that was supposed to

strengthen that recalcitrant 4th finger we

all have. It was an age full of such efforts�failures,

all.

The marriage

produced eight children, and seemed very happy, when

one of them wasn�t miserable. Clara did go on to tour

Europe, and become easily the best female pianist of

the age, and possibly the greatest period. Being of a

more refined, Apollonian nature, she probably missed

fewer notes than Liszt and Thalberg, her chief rivals,

even if general audiences might have found her less

thrilling.

But Robert

was having troubles. He tried to conduct an orchestra,

but the rehearsals were a disaster. For all of the

extremely fast tempi that litter his early piano

music, he wanted the men to play slower and slower. He

began to hear the sound of an A in his head that

wouldn�t stop. One note, the ghost of Mendelssohn

dictated to him the theme for a violin concerto. The

only problem is that Robert had already written the

concerto years earlier.

And then

there was the river, and the bridge, and the fisherman

who fished him out, and the asylum where he spent his

last three years. He had cast off his wedding ring and

did not seem to recognize his wife anymore. A young

prot�g� came to visit sometimes. His name was Brahms.

There is a

saying that if you knew how the sausage was made you

wouldn�t want any. Perhaps it is easier to enjoy the

music if you don�t know how much suffering was

involved in its production. Yet much of what Schumann

wrote must have been written during periods of joy and

contentment.

The end was

not happy. Mere mortals can shudder if they like and

thank their stars that they are not geniuses like that

and are not condemned to suffer for it, for after all,

shouldn�t a high price be exacted for the exalted

privilege of making art like that? But whatever our

lot, we have the music of Robert Schumann, and are

richer for it.

|