|

archived writings

on music: part one (Jan-June 2009)

current page / newer posts

(Jul-Dec 2009) / Jan

2010-May 2011 / June 2011-

contents

of this page: Mailbag (questions I've gotten from readers)

/ That reminds

me of something (thoughts about quoting

popular tunes in classical music) / Beethoven on Facebook

(a romp through a parallel universe) / My

Apologies (stress and predictability in

music) / What's with

all the Italian? (Why so much about

classical music seems to be in a foreign language) / The rest is silence

(how silence is important to music--and sanity!) / Know Your Limits (how

Chopin's strengths and weaknesses helped him forge a

unique musical career) / The 'F'

Word (thoughts on Musical Form)

Mailbag

posted May 16, 2009

Hello again. This assemblage of words is brought to

you for another month by one human being whom you

may never have met and who conceived and executed

thousands of tiny maneuvers with his hands at a date

and time several weeks in the past, then posted them

to a machine which is there to serve your need for

reading material at any time of the day or night in

whatever part of the world you happen to reside.

It all sounds fairly one-sided. I write, you read.

But as it happens, I sometimes hear from you guys

regarding things I�ve posted on my site, and this

month�s effusion is about that phenomenon. Even when

you don�t write I�m listening. But I�m getting ahead

of myself.

Being a creative artist can be a lonely business.

You might spend all day working on your craft, in

solitude (which is necessary to most of us) and

then, as most methods of distribution aside from

live concerts are pretty anonymous, you still have

no idea what sort of impression you are making. But

a while back, my web tracker informed me that the

site was getting a few thousand listeners a month.

Most of them are from China, and it appears that

they don�t visit the site, they simply hear the

music provided by an MP3 finder. They might not have

a clue who I am or care, but they are apparently

listening. The most popular musical selection on the

site is usually one of the Satie Gymnopedies, a set

of three short piano pieces written in 1888 by the

unusual Frenchman.

This is sort of embarrassing, actually. The

recordings where made some years ago in somebody�s

living room and the recording quality is not that

great. I was out of practice at the time too,

although that doesn�t seem as much of a crime under

the circumstances. I have vowed to make professional

recordings of these pieces and the others on the

site, and now that people are listening, I might

feel guilty enough to do it.

I have listeners from all over the world, and while

China is topping the list pretty consistently these

days the list also includes Germany, Austria,

France, Taiwan, Belgium, the Netherlands, the

Russian Federation, the Czech Republic, and a place

called Old Style Arpenet. Ever heard of it? (I

looked it up and it actually refers to an archaic

organizational scheme on the world wide web; it is

not a country at all, except in the minds of

nostalgic codgers.) Most of these folks remain

anonymous, but I have occasionally heard from them.

My music often seems to pop up on Spanish-language

blogs (often uncredited), and I was practically

knocked over when one fellow wrote to ask my

permission to link to some of my recordings on his

blog. We had a polite exchange, during which he

lamented his poor English and wrote that "language

divides us." I still haven�t brushed up my Spanish,

though I tried a little by reading his blog for a

few days. Meanwhile, we have music in common.

One day, someone wrote in about a strange little

piece that was wildly popular with amateur pianists

in the 19th century that I posted on my

site (the article and the recording can be found here). It is called the

"Battle of Prague" and the silly depiction of war

has found many mentions in the literature of the

period as well, since it was so pervasive. As far as

I am aware, mine is the only recording of this piece

on the internet, although it was dashed off on my

living room piano one morning before breakfast. I

ought to make a better recording of it, too,

although the music hardly justifies it. The person

who sent me the email told about his ancestor

playing the piece in their old country house in the

early 1800s and his excitement in finding a

recording of this now elusive piece which he could

play for his relatives, fresh from my Yamaha. It is

nice to feel you are doing someone a service now and

then. Apparently the house�s old ghosts also got to

hear it again after more than a century.

Since I can sometimes track "referrers" to my site

(the sites that direct traffic to mine) I can find

out sometimes who (in general, not in particular) is

listening to my files even when they don�t introduce

themselves. Once a selection of mine was on the

website of a college run radio station in Montana. I

don�t know if my recording made the air. The piece

in question was Handel�s Chaconne in G, which is a

good choice, since it is from a live recital on a

nine-foot Steinway in a nice concert hall and

recorded by pros. The performance is also decent. I

am glad it is currently in the number two spot in

popularity.

I notice that some of my recordings have also been

accessed by home-schoolers, which is pleasant, since

I�d like to support education any way I can. If any

of you feel like dropping me a line about your

endeavors, feel free.

Of course, it isn�t just the music that finds an

audience. There is probably the equivalent of a

small novel (400 or so pages, I�d guess) on

Pianonoise. While it isn�t generally of the dry,

encyclopedic nature, people with questions still

seek definitive answers on the site. They don�t

always get them, I�m afraid. One person wanted

instructions about how to build a hotdog stand. I

still haven�t obliged.

There seem to be a lot of questions about Beethoven

lately. "Did Beethoven worked for a government?

(sic)" I have no answer to that one besides, "no."

Someone queried "Beethoven and paying attention."

"What did Beethoven look like?" I�ve got a whole

article on that one. Some years ago some

inspiration-seeking soul wanted to know "how

Beethoven overcame his deafness." I�ve finally

decided to answer that one.

He didn�t. He went deaf. He stayed deaf. What he

did with his deafness is what is instructive. He

thought about killing himself, but he didn�t.

Instead, he kept on doing what he was doing before

he went deaf, which was to write the best music he

knew how. He could do that, because like many

musicians, he knew what the music he was writing

sounded like without having to physically hear it.

If you can hear the words you are reading you can

get some sense of what this is like. Since Beethoven

began to go deaf in his early thirties, he had to

live with this problem for nearly three decades. He

had plenty of time to rail against God, curse his

fate, and write masterpieces. He did all three. If

you are looking for a saint, it isn�t Beethoven. If

you are looking for easy feel good stories about

overcoming all odds, it�s not here. Sorry. But

Beethoven managed to do more for western musical

civilization in those years than most of those who

had two good ears. What role did his affliction play

in this, for good or ill? Who knows? If someone is

suffering from something and needs a role model,

just keep this in mind. He didn�t throw in the

towel. He didn�t give up. He kept at his mission in

spite of everything. It wasn�t picturesque, but it

was a miracle. Just not the sanitized versions you

see on television. Maybe he kept at it because he

had no acceptable alternative. Nothing fell from the

sky, though. He just kept working. It wasn�t fair,

and he knew it. And did his best with what he had

left. Which turned out to be plenty, we can say in

easy retrospect.

By the way, if you happen to be deaf, there are a

lot more options available than there were to

Beethoven. Everything from hearing-aids to cochlear

ear implants, for starters. That is assuming you

want to stop being deaf. Beethoven probably would

have pursued any treatment available. How would that

have changed his life and the course of musical

history besides giving us one less Romantic myth to

drown out the music itself? Another unanswerable

question.

While I may get a bit testy regarding questions

which seem designed to find easy answers to life�s

most painful realities, I confess to being downright

perplexed about this one: "Why do people have

fingers?"

At present, in my best objective, unbiased,

perfectly formed opinion, it is to be able to play

the piano. Throwing a baseball could probably be

done with a few fins on the end of each arm, but I�m

not a medical expert.

Do you have any ideas?

You know where to send your answers. You�ll need

your fingers to formulate them, most probably.

[email protected]

That reminds me of something

posted April 25, 2009

Back in high school I was getting my first real

education in classical music. I was listening to

Mahler�s First Symphony for the first time when,

part way into the first movement a popular klesmer

(or Jewish folk) tune asserted itself. I didn�t know

what it was until years later when a friend of mine,

who is in a klesmer band, happened to be playing it

one afternoon and I recognized it from the symphony.

Even though I didn�t recognize the tune, I could

tell it was a quotation of a popular folk tune by

the way the style of the music changed. I was a

little shocked. This was a symphony. Were symphony

composers really allowed to do that?

One reason for this attitude was surely the one

that I had been cultivating nearly since I had first

becoming acquainted with such music. Classical music

is supposed to be hermetically sealed off from the

other kinds, the more �vulgar� or �popular� musical

styles since it would only dirty itself by the

association. I imagine I absorbed that attitude by

osmosis from the people who were playing the music

on the radio or talking about it on record jackets.

Another reason for the separation, besides being

too holy to commerce with other styles, is the

baggage that popular associations bring into an

original composition. There have long been people

who believe that music can only be approached as

music, and cannot have any meaning apart from the

notes that make it. Referring to something outside

the piece itself may mean that the piece is trying

to position itself in dialogue with some other

tradition or ideology, or that it is trying to tell

a story or set a scene or say something socially,

and that very notion bothers some people to the

core.

While it is understandable that the idea of

�extra-musical association� should be treated with

some caution, since it can certainly be abused, I�ve

always found myself bothered by the absolutism in

the notion that music means nothing but itself. If

it is not to be connected to any other human

activity, how much relevance can it have?

Arguments about purity aside, however (and they

have existed in regard to everything from music to

human beings, often with the ugliest possible

results) there is still the thick line which needs

to be crossed between high culture and low culture,

a line that many disciples are making sure remains

indelible.

I don�t mean to suggest I am a fan of the current

crop of experiments in fusing hip-hop with opera or

making the symphony rap a little to attract

customers. Hybridizations like that can be done

well, but they usually aren�t. Maybe they are

harmless, but they are probably not going to have

much of a lasting impact.

But symphonies and sonatas have been doing commerce

with folk and popular styles for quite a long time,

and most of classical music�s recognized masters

have been responsible for at least occasional

dabbling, if not a more studied approach.

Particularly in the 20th century,

quotations �from the people�s music� have become

part of the symphonic vocabulary, for a variety of

reasons, from composer to composer. American

composer Charles Ives made it a particular obsession

to snatch tunes from the musical world around him,

and rarely invented one of his own. But even the

champion of absolute music as his defenders thought

of him, Johannes Brahms, engaged other musics even

in his symphonies. He did it more subtly, so that it

was simultaneously part of the musical fabric of his

piece, and he usually chose other �art music� to

quote from.

Bela Bartok took a more scientific approach,

cataloguing and arranging many of the tunes from his

native land, capping a popular trend in the 19th

century to take interest in and make �artistic�

settings of traditional songs from one�s own

country. It was a time when what made your own land

unique was no longer something to be embarrassed

about. I don�t recall whether Bartok actually used

any of the tunes in his symphonic works the way Ives

or Copland did.

Use of these tunes can set up a �third dimension�

in the music, A way that the artist can use common

property, or a shared tradition to comment on it in

a new context. Often these songs have a kind of

�authenticity� about them, since, whether they

really originated from the people en masse or not,

nobody knows who wrote them anymore, and thus shorn

of any �taint� of having been written or created by

a professional, they are now on everybody�s lips and

by use and custom and context they have been

invested with meaning. Perhaps many meanings, not

the least of which may be a national or group pride

in being who you are (or think you are). And even

though we 21st century Americans love to

exult the individual, we still feel it safer to hide

in numbers�Democracy, after all, is about the rule

of number, and capitalism is all about catering to

that mass. Something that can be sung by everyone

will seem to belong to everyone�and a Mahler

symphony certainly does not belong to that category,

even if a few bars could be made into a hit song,

and I don�t know if anyone has tried. Some�probably

most, �classical� themes are largely immune to being

translated into popular music, since they would have

to be tortured beyond recognition to fit into the

scheme of the popular song. A few have undergone

this surgery anyway. During the middle of the last

century it was more fashionable to be a proponent of

�good� or �classical� music, which created a demand

for �difficult� music that could be �made easy� by

stripping it of most of its artistic properties so

that it could pass for a valuable antique you could

get at Wal-Mart.

Quotation�s cheaper cousin,

appropriation, is fond of these experiments in

taking things out of their original context so that

the perceived value of the old object benefits the

new one, or for no other reason than that it sounds

cool. Such streams of consciousness are easier than

the discipline of formal cohesion. The question when

confronting an artistic use of quotation is how it

functions and what layers of resonance it adds to

the piece.

Beethoven on

Facebook

posted April 3, 2009

Step with me into a parallel universe.

Technology got here a little faster, or art

didn't--anyway, it is 1828 and this blog was

just posted on the internet. By the way, the

incidents mentioned below are based on actual

episodes in the life of Beethoven:

It�s been nearly a year since one of music�s most

fascinating people passed away, and we are all

still really bummed out about it.

I first met Beethoven one night when I was

surfing for some cool videos on Youtube. He was on

some list of people with crazy hair. They had a

clip of him yelling at his landlady. It got a lot

of hits. I favorited it. So did all my friends. It

was about a year later that I found out he was on

Facebook. I had no idea he was into writing music.

Apparently it is the kind that nobody listens to

because it is really long and you can�t dance to

it. Some people started a �fans of Beethoven� page

and tried to get him to interact with them, but he

was kind of snotty and reclusive. I think this was

just after he had uploaded several of his early

works and discovered that the one that was getting

the most hits was the Choral Fanatasy, and that it

was probably because it had the word "Fantasy" in

it, and a lot of guys were hoping it was

pornography. As a result, they only listened to

the first three seconds and quit after they found

out it had some not very sexy violins in it. He

posted a nasty letter about it one night when he

was feeling angrier than usual, but he later

confided to me that he had learned something

valuable from the whole experience, which was that

if you want people�s attention you had better grab

it fast. He played for me an arresting little idea

of four notes that he was hoping to use at the

beginning of a symphony. da-da-da-DAHHH! I wish I

could remember it better than that. Unfortunately

he never got around to finishing the symphony.

I think he was kind of busy with all the stuff on

Facebook. He was a really lonely guy and he kept

friending people all over the place, but he lost

them faster than anybody. I don�t think it helped

much the time he posted the Heilegenstadt

Testament online. This was a rambling document

about how he was going steadily deaf and how

depressed and isolated it made him feel. He was

even thinking about committing suicide. Several

people wrote what a downer he was being. But, he

decided, he needed to keep composing, because he

had lots more stuff to write. He put some of it on

Sibelius.com, but nobody really liked it much

except for this one guy who kept going on about

how great it was, I think he was called

[email protected], and he struck us

all as a little weird. He liked to talk about

details in Beethoven�s orchestrations and his use

of sudden modulations like he was all that, which

I think ticked Beethoven off a little. But then

some theory professors started getting into it

with him. He must have spent hours posting nasty

things on their walls and throwing sheep at them.

They were convinced that he was doing horrible

things to music and he needed to just kill himself

in a particularly grotesque way, because that�s

how people talk online, you know? I don�t think

they actually meant it. I mean, other than that

they hated his music.

After a while Beethoven only posted in all caps.

I think he felt like he was shouting at the world

to overcome his deafness. But believe me, you

didn�t want to get into a discussion with him

about art. He seemed so depressed, though, that we

tried to take his mind off of it. We kept sending

him links to viral videos and dancing hamsters and

saxophone playing walruses and guys fighting each

other with mattresses and stuff. I suggested he

set some of those to music, but he wanted to work

on some ballet about Prometheus. Still, it seemed

to help. Sometimes he would spend all night with

us in chat rooms goofing around. I think after

awhile he was writing less music.

This was probably a good thing because I think

that was what was making him depressed in the

first place.

One time he wanted to rent a theater and have a

concert of a bunch of things he had written. I

told him that it would be much cheaper to just

make MIDI files out of all of it and post it

online. That way, nobody gets sore at you for

making them sit through a long concert in a cold

theater, and you don�t have to pay the musicians.

He grumbled about it, but he posted the files. I

don�t think they got many hits. For one thing, the

titles were not that interesting. Consirto and

so-notta were his favorite titles. Somebody wrote

in the comments section to his blog "that is

so-not-a piece of music!" He really went off on

that guy.

That was before he got the webcam. He used to

stream his musical improvisations. They were

pretty popular for a while, but mostly because

people wanted to laugh at his hair. He really

could have used a comb once in a while. Then he

got a page on Myspace. The thing I remember about

that was how loud the music came on when you

opened the page. Everybody was just yelling.

One night he wrote on my wall that he was working

on a Symphony about Napoleon. I don�t think he got

very far with it. He used to start a lot of things

and then wind up in chat rooms and answering posts

from people. There was this time he was walking

with a student of his in a garden and he kept

humming this wild series of notes that he had come

up with, but when he went to write them down he

noticed his laptop was open and some guy wanted to

chat with him about how his music really sucked or

some other sophisticated observation like that and

he forgot what he was doing for eight hours. When

he got to the piano the idea was gone. I guess

that must be why he only wrote eight piano

sonatas, which is a lot less than Mozart.

Besides the two symphonies he wrote, the eight

so-nat-as and about half a piano concerto, he left

behind a lot of pieces he complained weren�t

finished yet, although they have enough music in

them for several television commercials, which is

what we think he really should have been doing. We

are going to try to upload as much of his music to

Youtube as we can if his estate doesn�t stop us.

Then there is this guy Schindler, who is a real

pain in the ass. He calls himself a friend of

Beethoven and he is a real control freak. He is

not very kind to the online community as a whole

and he doesn�t care who knows it. I�m afraid he�s

going to find a way to shut down Beethoven�s

Facebook page. That would be too bad. A lot of

people are leaving notes about how much they miss

him, hair and all, and I think it�s safe to say

the internet won�t see anybody like him in a long

time.

My

apologies...

posted March 29, 2009

It appears that, in these days of

turmoil and anxiety, while recklessly and

heedlessly pursuing my vocation, I have been

unduly stressing you all out. Mea culpa. Also, I

should apologize for doing it in Latin. Bad form.

The reason for my rather late

apology is the epiphany I had while reading the

paper last week. While in transit from

Indianapolis to Champaign, I stopped in a small

town and picked up a small newspaper to go with my

side of fries. The opinion columnist had written

about stress in the age of recession, and

illustrated one of her points with a discussion of

a famous laboratory experiment involving rats and

electric shocks. There are probably, at this

writing, a number of students in the sciences who,

on the basis of the good old days, would like to

major in rats and electric shocks, and are

displeased to note that things are being done

differently these days. I hope so, anyway.

Anyhow, the rats were divided

into teams, and the first group received warning

signals before the shocks were administered, while

the second got no such preamble. The second group

developed stomach ulcers of greater size

than the first, which led the scientists to

conclude that not being able to predict the onset

of such scientific outbursts was stressing the

second group of rats out more. Ergo,

predictability makes life easier to swallow.

Which is why, predictably, my

mind went to music, and to the fact that most

popular forms of music are eminently predictable,

being made up of vast amounts of repetition,

whereas the styles in which I specialize, most of

them lumped under the umbrella term classical or

jazz, are not so predictable, because once a

composer or improviser has said the same musical

thing a few times, he or she decides to go and say

something else, often for what the listener may

feel is a very long time.

There are various ways to combat

this anxiety producing tendency. One is to listen

to the piece enough times that you become

thoroughly familiar with the contents--assuming

recordings are available and you have one. Or you

can go to a lot of recitals. One year I noticed

that every pianist who came through town was

playing the same Beethoven sonata on his or her

program. I imagine a dedicated concertgoer could

get that piece memorized by the end of the season

at that rate. Then there would be no surprises,

even in a piece a half hour long. Even in a piece

by Beethoven. The man does like sudden changes in

volume, after all.

Essentially, you are reducing a

long complex piece of music to the same kind of

narcoleptic that a popular piece provides by this

strategy. But your mind does have to work harder.

The average piece on the radio these days has

about 10 seconds of different musical information

in it, with the rest being repetition. That means

you can shut off your brain pretty fast and have a

stressless good time not having to adapt to

anything new. I wonder if anyone has done a study

relating classical music to the risk of

Alzheimer's. My guess would be that it helps fend

off the disease, since it helps keep the brain

limber. How many other secrets to the good

life are available to those whose brains function

at higher baud rates?

But if you really want to

eliminate stress, you'll have to enter into a kind

of conversation with the music. It might seem like

the long way, but then, memorizing every piece of

music you ever want to know can't be much shorter.

By learning the ways in which music is put

together, you'll have a pretty good sense of what

to expect, and what is really a surprise. Not

having any way to understand a stream of notes

other than that they sound pretty means pretty

much everything is going to be a surprise. That

would be the goldfish approach to classical music.

Goldfish are said to have about a three second

memory, so they can swim around the same bowl

endlessly and not get bored. 'Hey!' they say with

glee. 'What a fascinating rock formation. I hadn't

noticed that before. Hey...'

There are a lot of things to come

to know about this. There are as many approaches

to music as there are composers. Many more, even.

But there are common tendencies. Grammars,

spellings, rhetorical flourishes, three-point

sermons. You can, for instance, have a pretty good

idea when you hear certain chords what chord is

coming next. Or what melodic fragment or rhythmic

idea is likely to follow. You can learn to

anticipate important places of repetition and

learn to cherish variety more and more. If you'd

like a hand in this, I'm starting a series of

ear-opening experiences in which I'll take a piece

of music and discuss things to listen for.

Building on such experiences means your ears will

learn how to deal with music much the same way

they deal with English. You certainly don't know

every word of this essay, nor are you planning to

memorize it. You don't need to. You know what I'm

saying and you can boil it down to its essentials.

However, this presupposes that

you want to make a sustained effort, much the same

way that people who write music in this genre make

a sustained effort to create their music. If you

don't, I guess all I can do is apologize for

making your life so complicated. But I imagine

most of you to whom this really applies have

stopped reading this blog a long time ago. For the

rest, all I can promise is an adventure. These

things seem very basic for me, but they may be a

shock to you. Recently I've been reminded of this

by posts on the internet expressing: 1) surprise

that musical style has actually evolved over

time and 2) the thrilling epiphany that

composers don't just string notes together until

they get tired of it, but actually plan their

compositions. I'll do what I can to make these

notions seem not quite so bizarre. You can bring

your questions. I'll do my best to answer them.

What's

with all the Italian?

posted March 15, 2009

Classical music seems like enough of

a foreign language to most people without having to

throw an actual foreign language into the mix. Unless

you speak Italian, the names of pieces: Sonata,

Symphony, Concerto-- instructions about how fast to

play them: allegro moderato, vivace, largo, and like--

and a whole host of markings within the pieces:

ritardando, espressivo, allargando, staccato, arco,

fortissimo, and on and on, might have you saying with

Mozart in the movie Amadeus "basta! basta!" (enough!

enough!)

So what is up with all of that

Italian? Did the guardians of the sacred tradition of

'good music' decide to put everything in Italian so

the rest of you guys wouldn't figure it out? Seems

like it, but no. However, the real reason for all the

Italian is equally stupid. Read on:

There are several things about

humanity that should not be underestimated. One of

these is the power of rivalry. On a small scale it is

known as 'sibling rivalry'; widening the lens a little

it is known as war. Countries and cultures have been

colliding practically since the days that Pangaea got

a divorce. But there is an interesting little

variant of this; if you can't wipe them out, you can

show you are just as good as they are.

We've always had people who have told

us who in the world is the best at something; these

are the people in the know, and what they know is that

they don't want to take a backseat to anybody. You've

probably heard France is the best place to get wine,

the Swiss excel at watch making, if you want

engineering, for God's sake, go with the

Germans. Aspen is a pretty good place to go

skiing, unless you live near the Alps. The list could

go on and on. Egypt is the place for

pyramids, if you are in the market for one. They are

probably going cheap, these days.

Now if you can't beat them, you don't

have to join them, but that would require inventing

your own thing to be good at, and that is a later

stage in the development of both people and

civilizations. In Europe of the 17th and 18th

centuries it was still the epitome of taste to imitate

the epitome of taste; the rich and powerful are never

makers of things, but they are astonishing collectors.

In luxury, the fellow who set the tone was the biggest

king on the block, which at one time was Louis XIV.

The Germanys at that point were divided up into about

300 little kingdoms, and they all tried their best to

be as luxurious and ceremonially wasteful as the court

of France, with, I'm imagining, some pathetic results.

Even Louis knew where to get his

music, and it wasn't France. Somehow word had gotten

around that the Italians were doing some hot stuff

musically. Probably their civilization allowed for a

greater development of the arts--remember that little

thing called the Renaissance? An Italian thing

(1400-1600). While the Italians were still basking in

the afterglow, the rest of Europe was just getting the

memo after two centuries. England had been too busy

fighting France for a hundred years and trying hard to

stay poor and disease-ridden, the German states were

riddled by wars and reformations--but in the southern

climes the arts had been given a better chance. Now if

you want to impress people, you need to find out were

the best stuff is, and steal it for yourself. Once

Louis figured that out, everybody in Europe had their

own music masters (the kings and princes, I mean) and

they were all Italian. Meanwhile, Italians were

streaming out of Italy trying to find work in the

newly created job market were there was a bit more

room to stretch your arms without poking another

Italian court composer.

Not all the Italians got all the hot

jobs; some non-Italians changed their names to sound

like they were Italians. How that fooled anybody I

have no idea (I guess Puck was right: 'Lord, what

fools these mortals be!'). At any rate, the Italians

were dominating music at a critical time, because it

coincided with the birth of several forms of music,

and the idea that you could write more on your page

than mere notes; a few remarks in a language that

people could understand more easily might help with

important things like how fast you wanted the music to

go, or how loud. These were also items that hadn't

been subject to flux a few short centuries previous,

at least in the minds of those who believed they knew

the eternal principles they called music to be, and of

course, what it wasn't.

If you were Italian, you naturally

wanted to write these instructions in your own

language. If you happened to be an English composer

(hiding under an assumed name) and you wanted the

music to slow down for a minute, you could, after all,

write 'slow down' but that would mean you were an

imbecile who didn't realize that Italian really was

the thing this century. If you wanted to argue that it

was better to be able to understand something than be

fashionable, you obviously didn't know much about

humans.

Fortunately for those too lazy to

learn a few words in another language, a counter-trend

soon materialized, which was the idea that one's own

country was just fine, thank you. Eventually it lead

to more wars, but for a while it merely excited people

with the notion that they could in fact use their own

language to communicate musical instructions in.

Beethoven, in the early 19th century, was one of the

first to make the change. One of his late piano

sonatas has the instruction 'Gesangvoll, mit innigster

Empfindung ' (singing, with inner expression) which is

a mouthful in any language (and pretty lonely;

virtually all the other instructions in the piece are

still in Italian). The fact that Mozart had already

written an opera that was not sung in Italian was a

hopeful sign in that direction.

When it came to marks like ritardando

(slow down) or crescendo (get louder) Beethoven kept

the Italian. Old conventions die hard, particularly if

they are easy to use. When it came to expressing

thoughts which did not have ready Italian words

hallowed by tradition it was easier to dispense with

the old custom. Some of my scores are a similar motley

of languages, two centuries later. One of my piano

pieces has a passage marked to be played 'like a pair

of angry bassoons' and I have no idea what the Italian

equivalent of that phrase is, nor would I wish to

translate it. It is no longer necessary to keep up

appearances, but it is still difficult to make a

complete break.

I tell my students that they are

going to have to learn the standard Italian markings,

but if they are composers it is not necessary to

always use them. I don't think it is a bad idea to

have to adapt, even if it seems like too much trouble

to learn all of those 'funny words.' Being an English

speaker does not make you the center of the universe.

But then, Italian isn't the only thing going either.

Many of Russian composer Alexander Scriabin's markings

are in French--and some very interesting ones at that.

Into the 20th century the elite in Russia thought the

French were pretty keen.

Cultures have a long history of

imitation, appropriation, influence. Until the 20th

century America tried to pretend it was Europe, for

musical purposes. Today most of our classical canon

consists of German composers--Bach, Mozart, Beethoven,

Brahms--all Germans (Mozart was technically Austrian).

This has long frustrated the heck out of our own

native composers, and our country isn't alone in this

German domination. For a long time it was fashionable

for our composers to go to Europe to learn their trade

and then come home and show us what they'd learned. It

could, of course, imply a respect and and interest in

another culture which, added to our own arresting

musicality (it took a European composer to complain to

us that we were neglecting it!) would make for a very

intoxicating musical brew. But I overestimate

ourselves. We are too busy keeping up with the

Joneses, or the Jonesos.

But the next time you are listening

to your German music with its Italian name, sipping

French wine and propping your feet on an Ottoman, just

think of all the cultures that have contributed to

your entertainment. Even the Sun King didn't have it

this good.

The

Rest is Silence

posted March 1, 2009

Hear that?

I�m hoping your answer is, "Hear what? I don�t

hear anything."

Don�t go adjusting your speakers. This page isn�t

making any sounds. I wanted to call your attention

to that fact. It�s silent. The impression I've

been getting from hopping around the internet

lately is that this page is one of the few ports

of entry to a musical website that doesn't dish

out unsolicited sound (often at high volume)

before you know what hit you.

Now, you may have some sounds going on in the

background. Maybe some other tabs are open and

they are making sounds. Maybe the television is

on, or the stereo. In fact, it would be a safe bet

that there is noise in your environment. I feel

confident that if I bet a $20 on it with every

reader of this column, I would gain more money

than I would lose. But do us both a tremendous

favor and turn it off for a minute. And listen.

I don�t mean to scare you. I know some of you

can�t handle silence. It has become so rare, so

unusual, that many of us just don�t know what to

do with it. And yet for others it can be a

precious gift. Or both, probably.

It may seem odd for a musician to talk about

silence. Music is about sounds, after all, right?

My mediaplayer seems to think so. The instant a

piece of music is over, it automatically loops

around to the beginning so it can start making the

same noise it did the first time. Generally, the

sonic effusions begin right away. We can�t have

any space between plays, can we? That would be, as

it is known in the world of radio, �dead

air.� Over in radioland commercials butt right up

against each other, and the host makes sure to

fill every second with some syllabic noise, even

if it is �umm� or �and.� Just like at the shopping

mall, or in restaurants. Whenever the live

musicians go on break they fill in with canned

music. Some of the patrons might get the shakes if

there weren�t musical vibrations smoothing our

path through the air�s rude molecules. Or we might

find out what mood we are really in.

I�m not alone among artists in my passionate

defense of dead silence. In fact, the first thing

we ought to do is call it living silence. Does

that change your perspective any?

Like visual artist�s use of �negative space,�

composers of challenging music have often written

silence into their pieces as an essential element.

Since, when we write music down, we have a whole

variety of symbols (called 'rests') that allow us

to represent exact quantities of this 'musical

nothingness,' it isn't impossible to call for

silence before, during, or after a musical

gesture, or a whole piece. All it takes is the

willpower, and, apparently, an unusual

imagination. One of the first places I remember

noticing this was at the end of Beethoven piano

sonatas. After all of the notes were over. The

last measure of these pieces is frequently the

following:

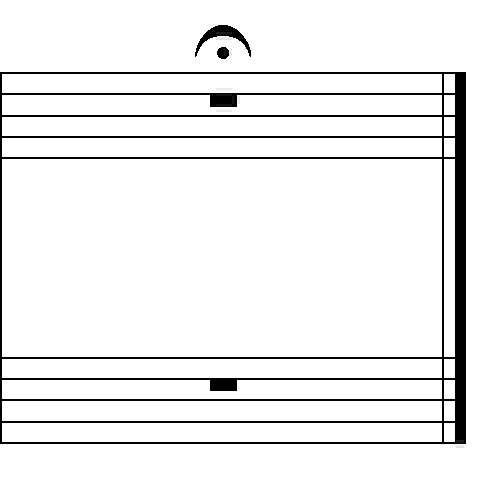

That rectangular blob up there is a whole rest.

It fills the entire measure, and it is compounded

by the little �birds eye� or fermata, up above,

which tells the performer he or she can hold it

out for however long they desire. It guarantees

several seconds of silence. The piece is not over

until this �border of silence� has been achieved.

Perhaps it is time for contemplation, or simply to

digest the foregoing contents. Silence often

speaks loudest after it has surrendered the floor

to an unfolding musical drama like that. Maybe

some of you will want to print that picture out

and put it on the wall of your office as a

reminder that you can hold the metaphysical

silence as long as you want to. While the world

around you rages on!

Beethoven gets a nod for beginning a work with

silence, too. One of the most famous musical

utterances of all time is the opening of his fifth

symphony. I�ll bet you don�t know that it actually

begins with a small amount of quantified silence:

That little item is an �eighth rest� and it means

the downbeat of the first measure is silent. The

notes don�t begin until the second eighth note,

and cause that little motive to sound, not like a

complacent little triplet, but a driven, rushing

motive that practically falls forward into the

next measure. The difference between putting a

rest at the beginning and not putting a rest in

the beginning is huge. Even though the rest itself

doesn�t make a sound, it causes the musicians to

think differently about the sounds they DO get to

make. And to pay attention to their conductor, who

will beat that opening downbeat so that the

orchestra can bounce off of a specific moment in

time that they can�t hear but must therefore see

represented with certainty, and sometimes a bit of

flourish, by their leader. I call this a very loud

rest. Sometimes rests are used in pivotal places

to rend the musical fabric open with shattering

silence, particularly if you weren't expecting it.

In this case, silence is very dramatic. The terms

'peace' and 'quiet' don't always go together!

The point here is that silence is an important

part of music. It isn�t easy to achieve, however,

since it requires a conspiracy on the part of

everyone in the space where the music is being

performed.

One thing that silence and music have in common

is that they are both purposeful. In between is

noise, whose function is chiefly to hold off

silence, but not necessarily to provide purposeful

music. It is basically aural clutter. I used to

hear my elders tell me �if you don�t have anything

to say, don�t say anything� but noise doesn�t

think that way. Its primary goal is to say

something, anything. It is there to provide

content, no matter the quality. So many things in

life seem to require this, that at regular

intervals, something has to be said or played,

something written, or filmed, or recorded. It

doesn�t matter whether it really has anything to

say; we aren�t listening anyway.

Do you think if we had more silence, we would

listen to the music we do have?

I think so. When you are surrounded by something

that intrudes on you constantly, it is hard to see

any purpose in it. And if we don�t see any purpose

in it, we think about it (if that is the way to

put it) differently. We probably even live

differently.

Even quiet isn�t silence. Soft, soothing music is

still sound. It may be relaxing, and I recommend

it as a stress reducer. But like many of today's

drugs, it has some drawbacks. Serious side-effects

may include forgetting to imbibe the sounds of the

world around you, or to have the courage to face

no sounds at all. Having built our artificial

society until it closes in on every side, it is

easy to forget there is a world out there that we

didn't create ourselves. Meanwhile, it is too easy

to indulge in Counterfeit Silence. The real item,

by contrast, is often dramatic, unexpected,

uncompromising. Try achieving some this week and

you�ll find out. Now, if you�re like me you are

probably 'hearing' the sounds of the words on this

page as you read it �silently� to yourself. So

I�ll shut up now, and you can take a moment to

remember what silence actually sounds like.

Pretty interesting, huh?

Know

Your Limits

posted February 19, 2009

My mother, an ordinarily sage woman

who has given me plenty of good advice over the

years, also threw out this adage on occasion: know

your limits. I�ve always thought that this was the

worst piece of advice she ever gave me. The reason

for it had a lot to do with the context. Whenever I

wanted to try something I hadn�t done before,

particularly if it was in addition to what must have

seemed to her like an already full schedule (this

was before everybody was on 8 soccer teams and judo

and ballet and piano and a travelling baseball team

or two or three and the debate team and the swim

team simultaneously; I was probably in marching band

and the tennis team and that was it�besides piano

lessons, of course) she would trot out this bit of

advice and I would invariably grumble �well, how am

I going to know my limits if I don�t get to test

them?�

In other situations, this advance

bit of caution would be a good idea. But it is

seldom allowed to really interfere with our decision

making process. So often in life we don�t really get

to know what it will be like to have the job, the

house, the marriage, the career path, the kids,

until we�ve already taken them on. It would be

helpful to have something besides a little bit of

advertising to go on before we commit to something

that we can�t really know until we are in the thick

of it. It would be helpful if people gave us more of

a clue. I remember thinking that a lot when I was

young. "So, what do you want to do when you grow

up?" the adults would ask glibly, and I was supposed

to just know without really having much in the way

of role models, real life examples, data�I couldn�t

even go to a web chat room to see what people were

saying about the things I didn�t know anything

about. I suppose in the absence of real data a

certain amount of blanket caution isn�t all bad. But

there is another reason we don�t always need to

worry so much about what our limits are. Other

people will tell us!

I have a bad habit of reading

biographies of musicians. In some respect this is

useful, because I am getting real information about

different responses to circumstance in the real life

choices that some of the greatest musicians in

history have made. In contrast to those gee-whiz

thumbnail biographies of �the great composers� that

get foisted on kids, where some incredibly talented

fellow springs from nowhere and his life is an

uninterrupted succession of triumphs which is why we

are exhorted to practically worship our hero, real

biographies written for grownups that explore their

subject with depth and subtlety can reveal all kinds

of fascinating things about the lives and

circumstances of some very different people. But

they are, invariably, depressing.

One reason they are so depressing

is that there is always a great deal of failure in

the subject�s life. It could be that the public just

isn�t that interested in what they are doing, and if

they depend on their vocation for money there is

inevitably a lot of fiscal anxiety. It could be

their critics, rivals, their own internal struggles,

failing relationships�sound like any human beings

you know of? Most recently, my reading list included

the pick-me-up story of Frederic Chopin, often

called the �poet of the piano,� one of the most

played 19th century pianists in concerts

today.

In the case of a biography

sometimes the same issues, chapter after chapter,

can seem almost as hectoring as they would have

living through them. In the case of Chopin, what I

remembered as something that was registered as a

complaint in the few public concerts he gave began

to seem like a faucet that wouldn�t stop dripping.

This was because Chopin gave more public concerts

than I had realized.

The incessant refrain was that

Chopin�s tone production was lacking. In other

words, he just couldn�t play loud enough. In an age

when cataracts of sound were the piece de

resistance, this was a problem. But not one Chopin

didn�t struggle to overcome, apparently. Throughout

the early part of his career, at intervals, he would

appear on the concert stage. Every time, his

reviewers would complain that he couldn�t command

the oceans of sound necessary to volley an

impressive squadron of same to the far corners of a

large concert hall. So he would try again. Same

result. After a while, he stopped trying.

Chopin had another problem too,

which was that he was not interested in writing

pieces that were simple enough for amateur pianists

to play, or to understand. Despite his

late-developed Polish patriotism, he didn�t write

any works that were obviously nationalist, which

would have also made him a big star, at least in his

native land. As a transplanted Polish national

living in Paris, he didn�t capitalize on the latest

dance craze to rake in the cash (look at the word

"capitalize"�the word�s very origins must have meant

turning a situation into money!). Between his

temperament, ideology, and limitations, he basically

cut himself off from the concert hall and the role

of popular composer. What did he have left?

What he had left were small,

intimate gatherings of friends and music lovers who

could appreciate his strange effusions. In a small

room where his 31 flavors of pianissimo could be

quite effective, and his horror of large crowds need

not interfere with his muse. This was known as the

salon, and it was also a rather popular movement in

Paris at the time. Critics of the concert stage

looked down on this music; it was considered a

rather vulgar thing in comparison to the high art to

which it ran parallel. But Chopin gave to it his

best works, which classical pianists are still

playing in droves and calling masterpieces. We play

them most often in the concert hall, which begs the

question of authenticity, but we still play them.

Chopin wasn�t like the extroverted,

larger-than-life Liszt, or the bizarre Berlioz�he

didn�t champion the Romantic gesture writ large with

a huge orchestra and long, dramatic tone poems or

tragic narratives. Despite what so many have written

since about great composers touching every genre

with their genius he wrote almost entirely for the

piano. Rarely is anything more than ten minutes in

length. There are shattering fortissimos (could he

play them?) but there are many intimate moments that

cannot be found in the music of anyone else.

Chopin carved out his own unique

role in the history of music. Part of this was his

own free will, and part of it was his choice,

apparently, to accept what his critics were telling

him, and to recognize that just because everyone

else thought music had taken up residence in large

halls with marrow-shattering orchestras and pianists

of steel, didn�t mean there weren�t other ways of

doing things�as if to suggest that the dominant

trend need not tyrannize where it could not be used

to advantage.

In other words, Chopin was formed

both by his successes and his failures.

Aren�t we all?

Music

and Math

posted February 1, 2009

This article has been moved to its

own page due to length

The F Word

posted January 20, 2009

There is a Christian pianist whose

online lessons I was reading the other day who had

some unflattering things to say about the importance

of structure in a piece of music. He pointed out

that there were in fact musicians who believed form

to be the most important thing about a composition.

This was in their eyes what made a piece 'good.' He

was offended by this.

Well, he should be. [Would it help

if I put sarcasm in italics from now on?] A fluent

understanding of the problems of Form isn't exactly

second nature to the majority of our Christian

pianist hymn-arrangers these days. It is a difficult

thing to master for anyone, and it requires much

more than moment-to-moment attention to a piece of

music. Most people don't know how to listen for it,

either. If you are creating a piece of music, it is

much simpler to try to make each moment as pretty as

you can, and not worry about whether it really adds

up to something in the long run. When this same

strategy becomes a philosophy of life we call it

hedonism. At least, when applied to a musical

composition, it doesn't hurt anybody.

My mission here is not to give this

gentleman a unilaterally hard time. In fact, if we

give his remarks a little more context, I have a

good deal of sympathy for his position. Between the

two sentences I've already quoted was the

characterization that these form-judging musicians

think that if you don't like their music it is your

problem because you wouldn't know good music if it

hit you with a two by four. I've 'adapted' his

comments a bit, actually. They weren't so colorful

in the original.

But the reason I want to start out

with a bit of sympathy is because there are indeed

many people who feel that it is their job to sort

out the ones who know from the rest of you bozos,

the exalted initiates from the boorish mob. This

musical Phariseeism is hardly limited to matters of

form, but it is a considerable plank in their

platform--or their own eyes. This topic is so

depressing to me that it deserves its own article.

It was almost a given that a new

piece of music during the 20th century would be

criticized for its structure. Critics, who had one

opportunity to hear something on the night it

premiered, loved to savage a piece that they

couldn't follow from beginning to end in the manner

in which they were accustomed. If the piece had any

surprises, the logical argument that they were

expecting to be dispatched in so many notes would

seem to be suffering, in their august opinions, from

a poor treatment of form. To put it in a nutshell,

anything new tended to throw these critics a curve.

If that originality extended to the way the piece

unfolded from moment to moment, or in terms of its

long-term plan, these guys wanted you to know that

their superior musicality could pick up on it. And

more often than not, they did not appreciate these

innovations. This is an illustration of a mindset

which worships at the shrine of what was great in

the past and does not welcome change. It is an

outlook that can be found in people of all levels of

intellect. But it also shows just how difficult it

is to understand form.

Before I get too carried away I

should define a few terms. First of all, every piece

of music unfolds in time. It is not present to our

senses in its entirety, but only as one part of the

whole. That whole, therefore, it has some kind of

relation between its parts, a structure. It might be

a pretty poor one; if it were a house, the roof

might fall in. But it is a piece of music and so

nobody dies.

This essay is also unfolding to

your consciousness in time. If you are asking

yourself questions like: what is the main point

here? or I wonder were he is going with this? you

are asking questions which are related to the form

(as well as the content) of this sea of words. Most

people do not read essays to see how well the author

connects what he says at the beginning with what he

says at the end, just as they are not paying close

attention to the form of the music as a separate

element. But if I were to just start off talking

about baseball right here, and in a few sentences

get bored and talk about the weather, or just start

typing gibberish, your mind would probably get very

confused and your attention would wander. If the

topic itself interests you and my writing is

sufficiently interesting, you'll probably stay with

me, as long as I seem to be going somewhere with

this. My treatment of form does have something

important to contribute to the success of this

essay.

Indeed, some of my points are

taking longer to develop than others. Some of the

sentences you've read are key to getting the drift

of the whole piece. Others are providing support for

those sentences. Others seem to digress a bit and

provide some local interest but could probably be

taken out and you'd still get the idea. All of those

things have to do with how well the words and the

thoughts they express cohere. And they all have to

do with form.

For some people form is essentially

a recipe. If you put the right musical moments in

the right order, you have an instant piece of music,

and there is no need to worry yourself over whether

the content or character of a particular piece might

seem to require that its structure be approached in

a different way. This formulaic approach to form is

what you learned in music class. Remember the old

letters: ABA? Some music happens, then some

contrasting music happens, then we return to the

first part and do it again. A formal approach no

subtler than that means I probably could talk about

baseball here if I wanted to, so long as I

eventually wandered back to the idea of form again.

This is called ternary (or three-part) form and its

various cousins, like ABACA and ABACADA, are not

variations on the killing curse from Harry Potter

but types of Rondo form, which is a way of vivifying

the idea that you can take a musical thought, wander

away from it, come back to it for an encore, wander

away from it again, locate it a third time--it is

still there! and do this as many times as you think

you can sustain interest (and if you want to

challenge our attention spans do it one more time!).

There is a whole other, more

complex, family of forms, which are closer to an

essay. In these, the theme or themes, which are

obviously groups of musical notes in this case, are

presented, and then developed--transformed in a

whole variety of ways which can either show off the

composer's cleverness or reveal a whole range of

emotional and intellectual possibilities for what

may have seemed a trifling little tune at first.

Usually these forms (referred to as Sonata forms)

are also symmetrical, meaning they return to

business as usual after the developmental section, a

form of ABA in which B is not a contrast but a

taking of A and running with it. This notion also

gives rise to variation forms, which are usually

self-contained sections featuring transformations of

a common theme, one after another. I've never seen

this done with prose, but it might be fun to try.

Even given this rather impressive

menu, some composers are not happy. This is because

we are creative troublemakers, although I repeat

myself. While a symmetrical form suggests

architecture (walls on both sides supporting equal

weight from the roof), narrative or dramatic forms

can also translate themselves into music, and these

forms do not like symmetry. How would you like to

read a novel in which the last chapter was an exact

copy of the first, as though what had transpired in

between had no lasting effect on what came at the

end? This is why there is often vociferous

disagreement about formal design even among people

who very much know what they are doing. The vast

difference in philosophy between forms which evolve

and forms which are essentially static also, I hope,

gives you a window into the near limitless variety

of formal structures and ideas about how to create

these musical blueprints, to say nothing of the

immense challenges involved in satisfactorily

molding a piece so that the form seems to come

alive, rather than being imposed on it separately.

If I were to do that, I might dispense with this

paragraph after I had reached a certain quota of

words, say the same number as in the last paragraph,

whether I had concluded my thought or not.

The next paragraph may or may not

pick up where the last one left off. Isn't this fun?

Continuity, discipline, resisting a thousand

temptations to just spew every remotely connected

thought I have while I write this onto this page

while I select the ones that are most likely to make

my points and take me to where I want to go--but

then this sort of architecture is probably of more

interest to writers and composers than it is to the

general public. I do think, however, that if people

knew something about the ways in which music was put

together it would at the very least keep them from

getting bored so easily during a long piece. It

helps to know where you are in the plot. Which is

why, in my brave insanity I plan to devote several

pages to various musical forms and what makes them

interesting. I don't know anyone who has made the

attempt successfully to talk form to the general

public, at least beyond a few rudiments that make

the whole inquiry seem as exciting as boiling water.

All of which brings me back around

to the pianist I was paraphrasing at the beginning.

While there were enough assumptions on his page to

discuss in several more articles, the one most

germane to the subject of form was when he advised

pianists learning to improvise not to worry

themselves about it. He seems to think that form is

something that leads to imitation, something that is

done out of a sense of duty--good music is supposed

to follow certain rules, and therefore we must worry

about such things even though we haven't a clue why.

I quite agree that there is a danger in this kind of

thinking. Either the result is in fact a lifeless

concoction, not because the performer was worried

about formal decisions in the first place but

because he didn't really understand how formal

design can be a living, vital part of a piece of

music, or the piece seems inappropriate in its

context (in this case, for worship) because the

performer is under the impression that in order for

his efforts to pass muster with the right people he

must choose a formal plan that is wrong for the

materials. He can't let his inspiration breathe

because he thinks that the 'imposition' of form is

supposed to reign inspiration in, and form is the

master, the contents merely slaves, or at least

dutiful servants. And he thinks that rules are

something you get out of a book and do what it says

to do. In such a world there is no creativity

because there are no decisions to be made when the

demands of form and content seem to be at odds.

There is only one 'perfect' model, rather than

thousands of uniquely interesting ways in which the

various large-scale structures are used by a

composer who is brave enough to experiment with

traditions, not by ignoring them, but by assuming

them to be living breathing things to which his

contribution is yet another adventure in risk and

reward. It is to this world, not the world of

formality or formalism or the formulaic (all words

that show a negative, and I would say, skewed, idea

of how lifeless attention to form is), that I would

invite the intrepid composer. I should note here

that one of our dear pianist's colleagues once asked

English composer John Rutter what was important in a

piece of music, to which he replied "form, form

form." I will assume he did not mean this as a way

to kill musical interest, and neither did the person

to whom it was addressed, who considered it an

interesting remark, and part of his musical journey.

|