|

A

Page-turner's survival guide

or how to make yourself an

invaluable friend to every pianist on earth

I suggested in one of my

previous articles

that there ought to be a place page turners could go to

complete their education; preferably at a music

conservatory where their achievements could be best

encouraged, closely monitored, the most opportunities

for practice, etc., but since no one has taken me up on

this yet I offer here a modest online tutorial for those

thrown suddenly into the fray who would like to enhance

their skills before the big night.

Some basics

| It is never

good to actually crash into the performer. Try

to sit far enough away that, while you can see

the music, you need not worry that a pianist's

sudden rush up or down the keyboard will earn

you a bruise that will hurt the next day.

Official concert position is so that the right

side of the performer is facing the audience. If

the piano lid is open the sound will thus

radiate in the direction of the patrons who have

agreed, by their presence, to accept the

consequences. This means that the page turner

should be seated on the pianist's left so that

he or she does not block the audience's view of

their idol. But you never know. Things may

function a bit differently for your setup. If

the piano is facing the opposite direction you

may have to sit to the pianist's right. It is

generally a good idea not to sit between the

pianist and the audience unless you are a really

good page turner and you think that at least

half the audience is there to see you. |

|

|

If you want to

be certain of your angle, ask the pianist to do

a couple of windmills while seated on the piano

bench. This will demonstrate the reach of their

arms and assure you that you are seated in a way

that they cannot possibly hit you. While seated,

that is. When you are actually engaging in a

page turn you will have to watch the situation

more closely. It wouldn't be a sport if there

wasn't any risk involved.

|

Actual page turning

If you are planning to make a life

study of this valuable skill this can be saved for our

next lesson. If you want to learn in a hurry, here is

what to do:

Some time approximating 5 to 10

seconds before it will be necessary to turn the page,

stand up. You should now be hovering a couple

of feet from the pianist, a little above his head. Not

your whole body, of course. If the piece is of

moderate to fast speed, stand

up when

the pianist has reached the

beginning of the last line.

Look for a nod from the pianist to indicate when to

turn the page. Most often, a pianist will want the

page turned just as he reaches

the last measure on the page, but this is a personal preference.

You may wish to ask the pianist about this. The

general rule of measurement applies if the pianist

does not nod, being a little busy with other things,

or has his own maverick way of doing things. I tend to

look down for a second so I don't get dizzy when I see

the page being turned. When I look up, I hope to see a

new page, having grown tired of the last one. When you

have turned the page, from the top of the page, being careful not to get your torso

too close to the pianist, and when you are certain

that you have only turned the desired number of pages

(generally being one at a time),

sit down, and politely wait your turn for the

next time. Lather, rinse, repeat as often as

necessary.

Figuring out where you are in the

music if you can't read music

Now, this last description presuppose a

few things. One is that you can read music. If you are

able or nearly able to play what the pianist is playing

you do not need my tutorial; you can inquire about

becoming my teaching assistant. If you have absolutely

no idea what the symbols on the page mean at all, don't

panic. Here are some things you can do:

Follow the words. If someone is singing words to

the piece you are to play, then you can simply follow

the text. I had a very good time one evening last year

at a school concert listening to one young lady who

had been commandeered to turn pages for me at the last

minute busily counting the measures under her breath

(fairly loudly), obviously rather concerned lest she

miss the right moment to turn each page. Since it was

a choral concert, I wanted to tell her just to read

the words the choir was singing and not to worry

herself about it, but the concert had already started

and I had other things to do.

If the piece is not texted, or if the

text disappears for a moment, you can do several things.

One is to count measures, if you are reasonably musical

and have some idea of the beat. It will give you, if you

are accurate, some idea of where the pianist ought to be

on the page so you have some idea of when to stand up.

Standing up too soon will give the pianist the

uncomfortable sensation of being at a lesson; standing

up too late means you may miss your opportunity

altogether. Obviously this window varies with the speed

of the piece. If you are able to key in to the tempo of

the piece, you have the added benefit of communing with

the spirit of the music. It is a good idea not to count

out loud. Or to tap your feet. Or to look like you are

enjoying the music too much. Unless the performers are

not very good. Then a large part of their stock in trade

may be looking like they love what they are doing so

much that their audience will be too annoyed by their

cheesy grins to take much offense at the noises they

produce. In which case, you may join in.

Very often, a piece will be

rather picturesque on the page. A florid passage will

look that way. If the pianist runs up the piano, the

notes will get higher on the page. Actually, it

happens the other way around--first the notes tell the

pianist what to do and then he does it. What is important to spot are

landmarks. If there is a

sharp contrast between lots of thick, black notes

joined together like foosball players, or clustered in

a squadron, and then suddenly the page becomes

peaceful, you will be able to identify that spot when

you come to it and know where you are, which generally

contributes highly to a page turner's peace of mind.

Contrasts of loud and soft are also useful; you may

wish to memorize these few marks:

ff-very loud

f- loud

mf- medium loud (which, in a strange

twist, is actually less loud than just plain loud)

mp-medium soft (louder than just soft)

p-soft

pp-very soft

There are extremes at both ends,

made by adding more fs or ps to the

porridge, and these are the most useful marks to

notice anyway, especially when one extreme suddenly

dissolves into another. If there is a mark like "subito

pp" after some blustering around, that "suddenly

very soft" will tell you exactly when you get there.

Some other things to notice, if you have several

instruments, are when one of them has begun to play

again, or has just stopped playing; mark your spot

there. You can see it when the notes start to appear

on one of the other lines. All the ones that" have the

same line running through them are occurring at the

same time; that vertical line joins them all together.

You may wish to simply follow the

profile of the melody. Don't hum. If the pianist wants

to hum, that's his business. Many of the good ones do.

So do some of the worst members of the audience.

|

|

If you are really cagey, you can

follow the pianist's gaze as he makes his journey

across the page. If he is staring a little to his

left, then he is still on that page; you don't

need to panic just yet. If he is short enough you

might be able to make out when he is at the top of

the page. Despite their good looks, it is still

advisable to look at the music and not at the

pianists. |

|

Matters of form and style

Some people would like to know why I've

asked that they stand up every time they are ready to

turn a page. If the page turns come in rapid succession,

the page turner may feel like she is playing "my bonnie

lies over the ocean" in front of an audience. But if you

don't stand up, you are liable, unless you are very

tall, not to be able to get your page to the other side

without nearly whacking the pianist on the side of the

head. You really need some height so you can turn the

page from the top, anyway.

Let me explain what happens if you turn

the page from the bottom. The pianist sometimes cannot

play his notes because moving his hands to the required

position means going through some of yours. This is why

you should really, at all times, permit the pianist full

range of motion, especially if you cannot read music

well, and don't really know that he won't suddenly

launch himself at the low end of the keyboard and catch

you off-guard.

There is a well-known incident

involving a pianist--I don't recall whom--who was giving

a concert at Carnegie Hall. The page turner kept turning

the pages from the bottom. After a while, the frustrated

pianist said in a hoarse whisper, "from the top!"

Whereupon, the indignant page turner stood up and

flipped the entire score back to the beginning. This is,

of course, an alternate meaning to the phrase, "from the

top", but it is not usually a good idea to do this in

mid-concert unless you are absolutely sure that you are

starting over, as George Szell did once when the

audience for a Cleveland Orchestra concert set a new

world's record for coughs during the gossamer opening of

the overture to Tristan and Isolde.*

I have, in my

time, had to play passages in different octaves when I

was prevented from reaching the right one by my page

turner; I have turned back pages when two were turned

by mistake, or none was turned at all; once, the page

turner sat back down, unaware that he had turned to an

empty leaf between pieces and I had to finish the

piece from memory. I have also played through my page

turner's suit jacket, when I could see the note I

needed just before he blocked it. Pianists have ways

of getting the music played in spite of the obstacles,

much like a running back determined to score a

touchdown even if he has to bounce off of the entire

defensive line before he gets to the endzone.

Intermediate Page-Turning

Here are a few

important exceptions to the normal flow of things.

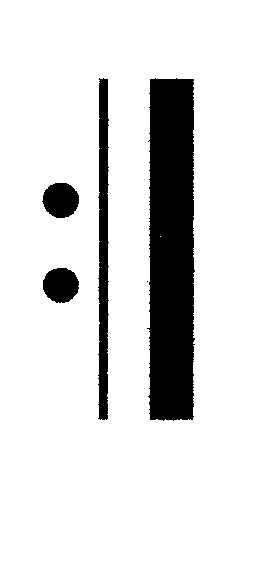

Page turning rule #9

If you notice

that right hand page has a double bar at the end

that

means the piece is over. There is no point in turning

to the next page; the piece will end with the end of

the page. When you see the double bar, you can let out

a sigh of relief (preferably inaudible), for your job

is temporarily over. that

means the piece is over. There is no point in turning

to the next page; the piece will end with the end of

the page. When you see the double bar, you can let out

a sigh of relief (preferably inaudible), for your job

is temporarily over.

If the piece

contains several movements (that is, separate pieces

that together are part of a larger work), those double

bars will still be in force. Not turning those pages

gives the pianist himself a chance to turn the page to

the next piece when he is good and ready; the

atmosphere from the last piece has a chance to

evaporate, and the pianist can control when he wants

to break the spell with an extraneous motion. We

pianists are a funny lot.

Important

exception to rule 9: if the page

contains said double bar, but it also has the word

"attacca" nearby, turn the page as you would

normally. "Attacca" means we are going to attack the

next movement without pausing in between. The next

sounds you hear will be a totally different piece,

but there won't be any time to quietly digest the

contents of the last one.

I'm going to

insert a bit of page-turning arcana here; there is a

mark known as V.S. or Volti Subito, which quite

literally means "turn the page quickly". This almost

never happens, and if you find the composer addressing

you, the page turner, directly, you should consider it

quite an honor. You should also be on your toes,

because there is very important information on the

next page that the pianist has to set his eyes on

pronto. As I said, you'll most likely never see this

mark, but if you do, you'll feel very proud of

yourself for recognizing it.

Now if you notice

that the pianist has a measure or two, or perhaps an

entire line, where he is not playing anything,

probably because some soprano has stolen the show; all

the notes are for her, but not for our poor

accompanist/hero, you should gracefully allow the

pianist to turn the page himself. This courteous

gesture allows the performers to assume control

themselves over when they are ready to look at the

next page; pianists do tend to have two perfectly good

hands which, when they are not busy pounding little

plastic levers, are just as good at turning pages as

the rest of us.

When you notice

that there is a universal rest (pause); that nobody is

making any musically required sound, and that the page

turn, should one occur, would be the only thing

audible in the concert hall, try to place it on one

side of the rest or the other to preserve the

atmosphere. If you have not been over that section

with your pianist beforehand, I recommend doing it

just before the rest. Sometimes I will instruct my

page turner to wait until after, confidant that I have

the next few bars memorized.

Turning a page backwards

There are cases

where it will be necessary to turn back to a previous

page, or perhaps to intentionally skip a few. When you

see a repeat sign it is generally too late to know

just how much music your pianist is going to have to

repeat, so you will want to watch carefully when you

see one of the following signs:

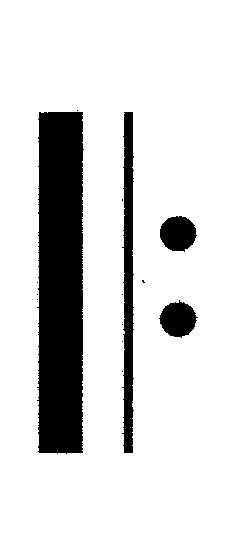

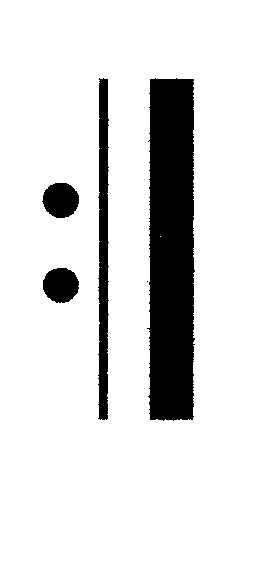

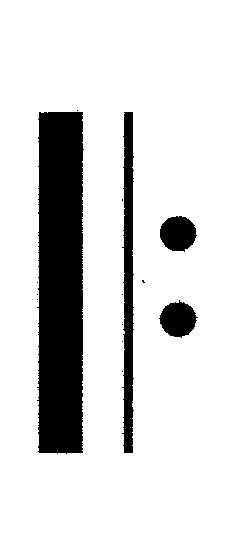

your standard "repeat" signs come

in pairs.

The

idea is that you have to repeat everything in between

these two signs! The

idea is that you have to repeat everything in between

these two signs!

Note: if you can

absolutely prove that you did not see one of

these

anywhere previous to

seeing one of these anywhere previous to

seeing one of these

, then you are to go back to

the beginning of the music. "Sonatas" generally do

just that with the first several pages of their

opening movement. , then you are to go back to

the beginning of the music. "Sonatas" generally do

just that with the first several pages of their

opening movement.

These are signs

you will definitely want to remember for later, for,

perhaps several pages down the road, you will need to

go back to that precise spot in the music. If you want

to pass your exam so you can enter the advanced class,

be aware that the test most certainly includes at

least one of these. If you are not in the mood for

such a workout, you'll certainly want to avoid pieces

with the word "Sonata" in them. These always have at

least one very prominent repeat in them, unless the

pianist has decided to ignore it. If the pianist has

not told you in advance whether he is going to take

the repeat you may wish to panic when the moment

arrives; be prepared to turn the page in either

direction, or both at once.

You can

immediately establish yourself as an expert

page-turner when turning pages for a piece called

"Sonata" by asking the pianist if he plans to

repeat the first movement exposition. Also, if one

of the movements is labeled "Scherzo" you will

probably have to return to the beginning of the

movement when you get to the end (D.C. means go

back to the beginning) unless the publishers have

written it out for you. (D.S. is that other kind

of nasty sign that means go back to the sign we

discussed earlier ( ) and proceed from there.) ) and proceed from there.)

Some other things

you will need to know to pass the advanced class: many

choral publishers like to put repeat signs only a

measure or two after the page turn which means you

will have to turn the page forward and then, before

you have had time to blink once, turn back to that

doggoned inverted repeat sign. But if you want to get

into the advanced class you'll have to sign up for it.

Here is our last handout, a handy guide to all the

signs that make page-turning life interesting. It is

always good to scan the music for these in advance

since all of our most aerobic turning will be done in

response to these; some page-turning divas like to

clog their routines with these kinds of things just to

show off and hog stage time. If you get a chance, ask

your pianist about the "road map" for each piece in

advance, or if she is "taking the repeats". If you

never get a chance to do this in real life you can

still sound like a dandy at cocktail parties by

dropping these phrases once in a while.

Really

Nasty Signs (in order of nastiness)

D.C. al

fine -- Go back to the beginning

of the movement; the pianist will now play the music a

second time until he is either too worn out to continue,

or he sees the Italian instruction for "finish"--the

word "fine", which is pronounced fee-nay,

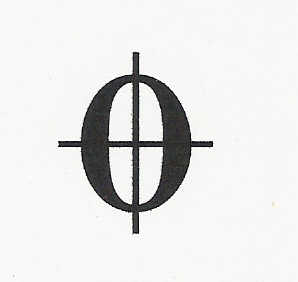

D.S. al

fine -- This one is a bit harder. It

requires you to look for a little symbol that could pass

for the coat-of-arms of an ancient clan of warriors,

namely--

if you are on the

lookout for this sign at all times, you'll spot it on

the first pass. Several pages later you will need to

know where this sign is. In addition to knowing what

page to flip back too, you should remember its location

on that page, in case the pianist is looking lost and

you need to direct her to that location. You will

instantly become recognized internationally by the guild

of page-turning cognoscenti.

The

pianist will now continue playing from the point of this

sign until the conclusion of the piece, "fine".

and of course, the

triple-axle of the page-turning world:

D.S. al

coda This works the same way as the

sign noted above, only, now instead of merely continuing

on from the point of the  sign until we've reached the end, there

will now be an additional sign until we've reached the end, there

will now be an additional

coda sign, which means we will now

skip all of the music in front of us and proceed

directly to the coda, which is the part that the pianist

didn't get to play earlier because we were too busy

skipping back to the coda sign, which means we will now

skip all of the music in front of us and proceed

directly to the coda, which is the part that the pianist

didn't get to play earlier because we were too busy

skipping back to the

sign. sign.

the page turner's

"triple Salchow" is a small variation on this, called

the D. C. al coda. I trust you can

figure out how this works. It will be on the test.

(By the way, if your

services are required for the accompanist of a singer

doing something from an opera, there may well be some

places in the music where the performers have chosen,

for reasons of their own, to cut whole sections out of

the music. This is generally marked with an elegant

pencil slash through the score. Try to find the next

similar-looking slash as best you can.)

to sum up: D. C. and D.

S. mean to go back; D.C. means back to the beginning of

the movement, D.S. to a particular spot marked with a

sign. (D.C. literally means da capo, or "from the head",

where D.S. or dal segno, means "from the sign") A coda

sign means to skip ahead to another spot marked with an

identical sign bearing the word "coda", which,

incidentally, means "tail" as in "tail end", although

some composers can go on for quite some time once

they've reached it.

Speaking of which, we have reached the

coda of this little article, so I'll leave you with one

nice thought.

Page-turning is a

high stress job and requires years of steady effort to

master; it is good to start out as an apprentice and

work your way up. If you are lucky, perhaps you will

be acknowledged in the program, or even asked to do

interviews on public radio.

In the meantime, you will

get a nice seat for the concert.

|