|

Looks Like it

Sounds--

or, those bizarre squiggles we call music.

(part two)

Why do we

write music the way we do and is it actually the

best method? Dare we ask?

part one

part three

I said

the last time that

clef signs were going to make things more

complicated. When Guido invented his system, the

little round block on the bottom line of the staff

always stood for the same note. It didn't matter if it

was a Tuesday, or the moon was full, or if you were

standing in Australia. Differing perspectives, or

reference points, didn't affect the material. If you'd

tried to even hint that it might, Guido would've thought

you were nuts.

If, for instance, you have learned

always to acquaint the round blob on the second line

from the bottom with the note G, it is going to be a

little disturbing when I point out to you that the same

blob, in the same location, could just as well be

several others. Similarly, if you were taught in your

very first music lesson that a quarter note is equal to

one beat, there will eventually come a day when you will

find out that that is not always true. We usually teach

beginners a few inalterable "facts" and then later, when

we think they can handle some conflicting information,

pile on the exceptions, and the differently oriented

systems. This nicely recapitulates the human race's once

cherished opinion that the earth was flat and the

unmoving center of the universe until the day we found

out that it was spherical and moving. At which point we

promptly assumed the sun to be the stationary center,

until it too got fidgety and started to dance around.

Doesn't anything hold still anymore?

Our journey through the ever expanding

series of lines in the last installment shows a bit of a

keyboard-bias on the part of the author, since many

instruments don't need to have staves joined together to

allow their full range to be written down, and it was

not meant to be a historical survey either because,

actually, the system of clefs we are about to explore

came earlier.

Bach, for example, almost never uses

ledger lines. Instead, he has a whole range of options

ranging from the employment of different clef signs.

A clef sign is a reference. It is

written at the beginning of a staff, and its often

florid design points at a particular spot on the staff,

which always stands for a particular note. From there,

the rest of the notes can be determined by how they

relate to the note that has been "fixed." Today, the

most common two clef signs are the "treble", or "G"

clef, and the "bass", or "F" clef. The G clef is

probably the most attractive looking clef, and is

written so that it encircles the second line from the

bottom of the five-line staff, which is henceforth to be

known as a "G". It is a particular G, the one commonly

known as G above middle C, and sounds like

this. You just have to know that. The

rest can be determined by working from the G.

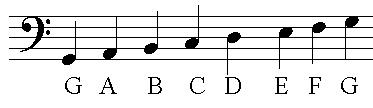

The F clef (or bass clef) works the

same way, only the two dots which follow this relatively

pedestrian looking shape are above and below the second

line from the top, marking that line as an F below middle C.

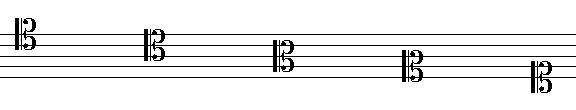

At one time, most musicians had to know

lots of other clefs. What most of those have in common

is that the squiggly line points to wherever middle C

happens to be on the staff. The reason having all of

these clefs is useful is that, if you have a soprano who

can sing a lot of high notes, and, say, few below middle

C, you will want your staff to make available to you

notes which are mainly above middle C. A tenor, on the

other hand, has a lower voice range, and, if you move

your reference point up, you allow room for lower notes

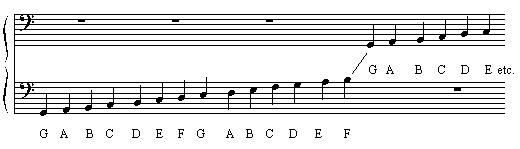

to be written. In other words, the higher the clef

appears on the staff, the lower is the range of notes,

which is how this chart makes sense:

The reason for all of this

monkey-business is so that you don't have to use ledger

lines (additional lines drawn above or below the staff

when needed to hold notes that don't fit in the staff's

range), which, at one time, would have involved more

work for your quill pen, or more expensive stamps for

your printing press. Nowadays nobody thinks ledger lines

are a problem, and this allows us to mostly focus on two

clefs, the treble and bass. The practical effect of this

is that reading music is much simpler, since there are

only two different clefs to worry about. Those alternate

clefs have not completely gone away, however, which is

why they still teach them to students in music

conservatories.

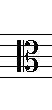

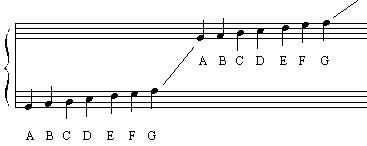

If you are a violist, for example, you

have to use one of these:

The reason being, I suppose, that the

poor viola has a range about equally above and below

middle C, and so whichever clef (treble or bass) you

chose to use, you would end up writing a ridiculous

number of extra, or ledger lines outside the staff. At

one time ledger lines simply weren't done; now, despite

their relative popularity, it is still a good idea to

have at least half of your notes actually on the staff

itself.

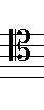

Outside of the viola, the bassoonist

needs to be familiar with this clef, to accommodate her

range:

One thing that is interesting about the

move from many clefs to only two is that it shows that

musical notation does not always get more and more

complicated throughout history. The practical effect of

all these clefs disappearing from common use is that

there are fewer competing systems to learn. This is not

so different from the way that most of the modes disappeared from

music around the 16th century. Instead of about 7

different modes and their variants, and theorists

begetting elaborate theories on how to use them, music

began to consist only of major and minor. E major, A

major, B-flat Major, all represent the same pattern of

notes in relation to one another, and share the same

guidelines about how to use those notes effectively. A

piece may be pitched higher or lower, but once it

starts, most listeners won't notice a radical

difference. Thus music has become simpler for the

listener. As of the 20th century, and on into the 21st,

however, those modes are back, along with a lot of other

diverse things. We live in a comparatively complex age.

In music and everything else.

strange clefs

|

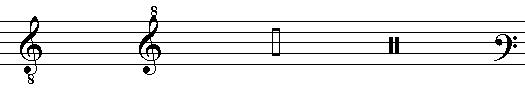

In addition to the

c-clefs above, there are several more interesting

clefs. Putting an 8 on the top or bottom of a

clef, like the treble clef in our first two

examples above means that every note that follows

will be played either an octave lower, or higher,

than it is written. The next two items are

actually for unpitched instruments like drums, and

do not point to any pitches at all, since there

aren't any. Different lines may be used for

different drums, however. |

The final item

should be familiar to any theory professor because it

appears to be an improperly placed bass clef, which is

a favorite of freshmen who don't know how to draw one

properly. It is in fact an alternative "baritone

clef." I had to look that one up myself. When I did, I

discovered several other rarely used clefs. There is a

table of them at

Dolmetsch theory online.

I don't agree, however, with the statement at the

bottom of the page that every one of the 19 clefs

shown is among those "most often used today."

I've got a doctorate in music and I didn't recognize a

few of them. If you understand how clefs work,

however, none of them is without a certain logic. The

"G-clef" family always points the way to G; the

"f-clef" family does the same for F; and the "C-clef"

family always shows you where to find C.

Most of us do not need to know these

alternate clefs. If you are only used to reading in one

or two, you may not even have considered how clefs as a

group function. A few people still concern themselves

with these evolutionary discards, however. Conductors

still need to know many of them. Composers writing for

certain instruments, as well as the ones playing those

quirky noisemakers. Organists who use older editions in

which the music has not been reformatted into modern

notation. But for the rest, life is pretty simple.

Not simple enough, though, if you are

just learning your way around. How come a note on the

bottom line is a G in bass clef and an E in treble clef?

Couldn't there be a universal clef?

I pose this question because I inhabit

the same body as the strange child who once thought up

a scheme for converting us all to "metric time."

The metric system was big in the 80s; everyone was going

to convert to it by the year 2000 (remember?). Since one

of its charms was getting rid of all those messy numbers

(5,280 feet in a mile? I mean, come on. How about a nice

round 1000 meters in a kilometer, whose name even means

1,000 meters, for Pete's sake.) I planned each day

around divisions of 10, with, I think, 100 minutes in

each of them. Weeks themselves could also have 10 days

in them (although that does seem a bit exhausting,

however long your weekend), But the earth herself didn't

seem interested in helping my effort, since I couldn't

get around the fact that while doing one orbit of the

sun it spins around in an unfortunately complex number

somewhere in the vicinity of 365. Anyhow, don't blame me

if you secretly long for only 10 hours in a day. I'm

sure my proposal would have been shot down by the people

who don't think they can get enough done with 12.

As it happens, the two staves that we

join together to create a grand staff, suitable for

piano playing, are really one continuous staff (see

part one for more

detail). But, there are seven different notes before the

series begins again, and a system of alternating lines

and spaces is going to need an even number if you want

the next octave to appear the same way it did the first

time. As it is, that bottom-line G makes its next

appearance in a space, like so:

The best I can do for you under

the present circumstances is to make each staff

consist of 7 lines rather than 5. That way, almost two

octaves worth of notes can appear on a staff, with

room for exactly one note between them, and then the

bottom line on the next staff winds up a G again.

Genius!

I suppose you are going to

complain that this is a bit hard to read.

Or...and I shudder at my brilliance,

let's cut one of the old five lines. Now we are back to

the original four lines as brother Guido knew them.

Maybe it was a mistake to ever add that fifth line in

the first place. Start with an A, while we are at it.

There is space for exactly one octave. No notes can or

should be written in between them. The top line of the

first staff is a G, and the very next note, courtesy of

the elimination of that no-mans'-land in between (in

other words, no ledger lines), is positioned on the

bottom line of the next staff. And the next note

is....do I hear an A?

Lather, rinse, repeat...it never

changes!

Let's face reality. It ain't gonna

happen. Custom has taken over. And besides, as we'll

find out in a couple of installments, there happens to

be some really useful flexibility about all this chaos.

Sometimes a systemic weakness later turns out to be a

strength.

on to part three: rhythm

|