|

Looks Like it

Sounds--

or, those bizarre squiggles we call music.

(part four)

Why do we

write music the way we do and is it actually the

best method? Dare we ask?

part one

/

part two

/

part

three

Harmony was something philosophers

liked to refer to long before there actually was any--in

music. It existed as a concept for many eons before

music began to feature it. It thus became the last of

what we consider basic elements of music to develop.

Before that, it was just rhetoric, like peace on earth.

At least, when musicians began to use

it, they already had a name for it.

One of the reasons for this

single-note-at-a-time approach to music for so many

centuries is that it requires a bit of coordination to

make two or more notes sound together and sound like

they ought to be that way. In fact, it wasn't until

music became a written thing that harmony began to

flourish.

(If by 'flourish' we mean every couple

of centuries somebody would add another simultaneous

event to the mix, lots of conservative voices would

protest, and music would lay low for a while to let all

the controversy die down. Once people got sort of used

to it, they could safely assume it to be the divine

order of things, and then the next crackpot musical

innovator would try something else and upset the apple

cart again.)

Something that is curious about that

system of lines and blobs that Guido developed is that

it is really quite adept at adjusting to the need for

simultaneous pitches. It wasn't designed for that, and

for a while, even when different voices sang together,

they tended to get their own staves, which meant that

each note got its own quarters, and nothing changed.

During the Renaissance (1400-1600) musicians often sang

together from enormous part books with the various parts

facing different directions so everyone could gather

around and sing. Otherwise there was little physical

evidence that the lines were part of the same

composition.

Combining staves wasn't necessarily the

problem--put several on a page, one below the other, and

draw a line on the left to join them together. But that

would require that composers think in terms of the

simultaneous combinations of sounds, and that,

apparently, required just as much of a mental revolution

as getting used to the idea that the earth didn't hold

still after all. Until then, composition manuals

instructed the would-be scribbler to write pleasing

parts individually, without worrying about the vertical

alignment of the notes. If the result sounded

aesthetically pleasing, all the better, but it wasn't

through trying!

It wasn't until keyboard instruments

got into the mix that it became necessary to place

multiple notes on one staff. Most other instruments

can't play more than a note at time, and several don't

want to! But a keyboard instrument is perfect for a guy

with 10 fingers that like to exult in their

individuality. The problem, of course, is fitting all

those notes somewhere. At first, this would have been

easy, since the only acceptable harmonies were fifths

and fourths, notes which are reasonably far apart.

But a few centuries later (don't rush

us!) triads came into view. On a keyboard, these

conglomerations of sound appear to be every other

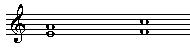

(white) note. And on the staff, it can be represented by

putting the notes in the consecutive spaces, or on the

adjacent lines.

Fortunately Guido left room for this

innovation by deciding that notes should go on lines and

in the spaces between them, so that an ascending scale

alternated between notes with lines through the middle

(musical shiskabob!) and those bounded by them.

[Actually, it occurs to me since I wrote that line that,

had Guido decided to only put notes on lines, we would

have the opposite problem--that of a three-note chord

taking the entire span of a modern staff. However,

half-step conglomerations would be easy to

represent--put them in the spaces. In which case we

wouldn't need accidentals!]

However, you can always get a modern

composer to muck it up. As forward thinking as this

accident was, it only lasted about a thousand or so

years. In the nineteenth century, harmonies, however

complicated, mainly stuck to chains of thirds--notes

still two notes up or down from their neighbor. But by

the twentieth, composers began trying things a little

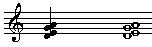

spicier. Now, trying to place a note on a space and the

one on the line immediately below it means that there is

not enough room for the circles without them mashing

into one another. This problem was solved by placing the

note-heads on opposite sides of the note-stems, like so:

Some composers decided they liked the

mashed-ness pretty well, and the tone-cluster was born,

in which every possible note that can be played should

be within the span of a certain area. Usually this is

done with the flat of the hand, or in the case of a

large cluster, the forearm, or, in the case of one piece

by American composer Charles Ives, a two by four!

This can be modified, by instructing

the player (usually in written instruction) to play all

the black keys or all the white keys within the range

shown.

That ought to settle things, if you are

being all-inclusive; however, if playing every note in

the vicinity is not your style, producing a very

specific clash may present still more problems. The

closer together the notes are, the harder it is going to

be to accommodate them. Say we want an A and and A-flat

in the same chord. Let's further complicate things by

putting in an F and an F-sharp.

That's what that little

number is for, with the very creative stem. Now where

stems were once simple lines, composers in recent

centuries have found all kinds of things to do with

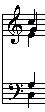

them. For instance, there is the issue of the double

stem, which goes back before Bach:

The reason for this has to do with its

position as a separate voice in the cacophony. We've

been discussing harmony as if it were a block of sound,

meant vertically, and indeed, all of those sounds that

go together have made written music grow very tall, as

if it were a bunch of skyscrapers in Manhattan.

But as I mentioned above, musical

simultaneity was at first viewed as the product of

happenstance--it was the forward flow through time that

was most important. If a keyboard instrument allows

several parts to be combined on one staff, that doesn't

mean they cannot be thought of as several parts, several

'voices.' Bach was very conscientious about giving the

separate parts separate stems, even if they formed a

chord (and even if it made the music look more

cluttered). If the notes could be drawn with notes going

in separate directions, well and good. If not, the note

was moved over ever so slightly to make sure that it

didn't have to share a stem with another note:

Thus, in a situation where one note

happens to be shared by two voices, it is logical to

give it two stems. And, in music before the middle of

the 18th century, it was rare that note-heads would

share the same stem. This, of course, is one of those

things that is confusing to piano students, and seems to

be taking the long way around. From the point of view of

the 17th century (and earlier), it was necessary to

justify each note as a part of a melodic line; not to do

so, treating it like a mass of sound, rather than as a

harmonious accident, was still a new and contentious

innovation. To us, it no longer seems like any big deal,

anymore than a car is a car and does not need to be

described as a kind of carriage that doesn't need horses

to power it, or a piano no longer goes by its full name

(fortepiano, or 'soft-loud', because it could do both).

It all depends on the place (before or after) from which

you are viewing the musical universe.

|